The United States abolished slavery 157 years ago – so no one since then can become someone else’s legal property. But one exception remained: the prisoners.

In most parts of the United States, slavery is still legal when it is considered a punishment for a crime.

But in the November 8 election, voters in five states—Alabama, Louisiana, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont—will decide whether to remove these exceptions from their state constitutions in an effort to outlaw slavery altogether.

The result may allow inmates to challenge forced labor. Currently, about 800,000 inmates work for a penny or for free. Seven states do not pay prison staff for most mandatory work.

Supporters of the change say it’s an exploitation gap that needs to be closed. Critics argue that this is an unsustainable change that could have unintended consequences for the criminal justice system.

‘I worked for 25 years and came home with 124 dollars’

According to human rights researchers, the roots of the modern system go back to centuries of African-American slavery.

In the years following the abolition of slavery, laws were passed specifically aimed at suppressing black communities and putting them in prisons where detainees would be forced to work.

Today, there are still black American prisoners forced to harvest cotton and other crops from the fields in the south where their ancestors were held in chains.

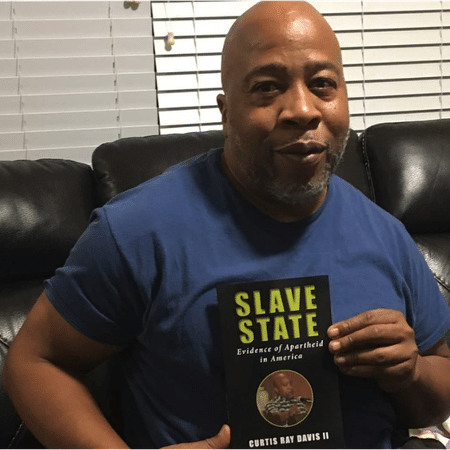

“There has never been a day in the United States where there was no legal slavery,” says Curtis Ray Davis II, who spent more than 25 years in hard labor in a Louisiana prison for a murder he didn’t commit, until he was suspended in 2019.

Davis had a number of jobs at the famous Louisiana State Penitentiary, nicknamed “Angola” after the country from which most of the enslaved Africans in the area were brought.

“I worked for 25 years and came home with $124. [cerca de R$ 627]’ says Davis. According to him, work done ‘against my will and at gunpoint’ has never taken more than US$0.20 (about R$1) per hour.

According to the Innocence Project, a group working to free convicted innocent prisoners, about 75% of the inmates at the prison were black. The group claims that American slavery in “Angola” never ended.

“Slavery was abolished, but in reality it was a transfer of ownership from legal slavery and private property to state-sanctioned slavery in the literal sense of the word,” says Savannah Eldrige of the National Slavery Abolition Network.

The organization is working to increase the number of states that outlaw slavery without exception, and is trying to persuade lawmakers in the US capital, Washington, to pass a similar law amending the US Constitution.

Since 2018, the states of Colorado, Nebraska, and Utah have taken measures to ban all forms of slavery. Eldrige points out that the movement has received support from both Democrats and Republicans. Only then was approval possible in the Republican-dominated states of Utah and Nebraska.

He estimates that by 2023, 18 state legislatures will pass laws banning slavery.

‘Undesirable results’

Few opposed the state’s efforts to eradicate the language of slavery. But the movement has met with resistance from critics, who say it would be too expensive to pay enough prisoners, that they did not deserve the same pay, or that the changes would put prisoners at a disadvantage.

In 2022, the California legislature rejected removing references to slavery from state laws in a 2022 vote in which Democrats, including the state’s governor, warned that paying inmates the state minimum wage of $15 per hour would cost more than $1.5 billion. 7.6 billion dollars).

The Oregon Sheriffs Association opposes the measure in the state. They argue that its approval will have “unintended consequences” and that all “refresh programs” involving low-paying tasks such as working in the library, kitchen and laundry will be lost.

The group claims these duties provide prisoners with something to do and “act as an incentive for good behavior,” a factor considered in parole hearings.

For the association, this measure poses two problems: it applies only to convicts, excludes those awaiting pre-trial detention, and could mean the termination of all prison programs not specifically authorized by court order.

“Oregon sheriffs do not in any way condone or support slavery and/or involuntary slavery,” the association says in a flyer sent to voters. He added that approval of the measure “will result in the elimination of all reform programs and increase operating costs for local chains”.

Large companies outsource

Prisoners contribute to the economy and supply chain in many ways, some surprising.

They have been asked to manufacture everything from glasses to license plates to park benches. They process meat, milk and cheese and work in call centers for government agencies and large corporations.

Companies that use a prison workforce can be difficult to track down, as jobs are often outsourced. A contracted company sells prisoners’ products and services to major companies that are sometimes unaware of where they come from.

Companies that only make use of prison labor in the state of Utah include American Express, Apple, PepsiCo, and FedEx, according to an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) report released in June.

At least 30 states include prison staff in their contingency plans against natural disasters and other social disturbances. They are fighting fires in at least 14 states, according to the ACLU report.

But if the measure passes, the lives of prisoners in the five referendum states are unlikely to change overnight.

“These referendums are necessary but not sufficient to end slavery,” says Jennifer Turner, a human rights researcher at the ACLU.

Courts will still need to interpret what rights prison workers have and whether released workers will receive sick pay to which they are legally entitled.

In states that have already eliminated slavery exemptions, the results are mixed.

A Colorado prisoner sued the state for allegedly violating the abolition of slavery. But in August, a court ruled that lawmakers had no intention of eliminating all prison labor and closed the case.

According to The New York Times, a prison in Nebraska began paying inmates $20 to $30 a week after the exception disappeared in that state. More legal challenges are expected to arise as prisoners continue to fight for their rights and protection.

Davis, who was wrongfully imprisoned in Louisiana, says removing the prison exception would end this “incentive” to detain his homeland’s citizens.

“I believe that anyone with a conscience, anyone who understands property law, understands that people should never be other people’s property,” he told BBC News. “And it shouldn’t belong to the State of Louisiana either.”

– This text was published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-63543395.

source: Noticias