An ancient gold coin is proof that the 3rd century Roman emperor, who was exiled from history as a fictional character, really existed, according to scholars in England.

The coin bearing Esponsiano’s name and portrait was found more than 300 years ago in Transylvania, once a remote outpost of the Roman empire.

Because the coin was believed to be fake, it was stored in a museum cabinet.

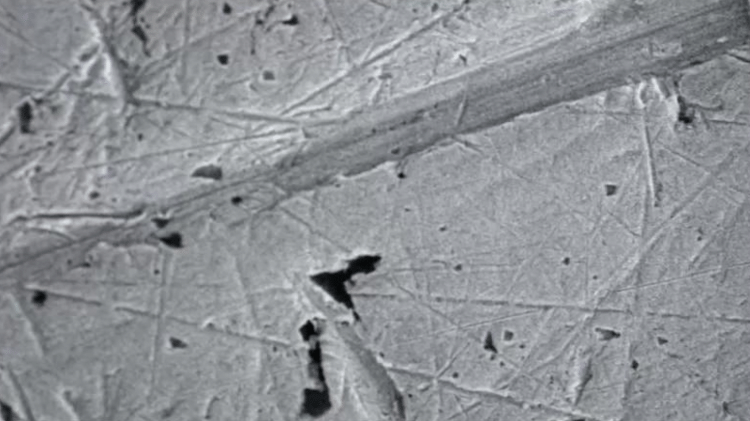

Now scientists say the scratch marks visible under the microscope prove that it was indeed in circulation 2,000 years ago.

Professor Paul Pearson, who led the research at University College London (UCL) in England, told BBC News he was surprised by the discovery.

“What we found is an emperor. He was a figure considered fake and rejected by experts.”

“But we thought it was real and played a part in the story.”

The coin was inside a small treasure discovered in 1713. Until the middle of the 19th century, it was believed to be a real Roman coin. However, experts at the time suspected that it might have been produced by counterfeiters due to its primitive design.

The decision to exclude the piece came in 1863 when Henry Cohen, then the leading coin expert at the National Library of France, considered the issue in his large catalog of Roman coins. He said the objects were “modern”, but poorly made and “ridiculously imagined” fakes. Other experts agreed, and Esponsiano was eventually ignored.

However, when Pearson was researching a book on the history of the Roman empire, seeing pictures of coins, he suspected something was wrong with these results. He was able to detect scratches on the surface that might have been caused by the circulation of the coin.

He then contacted the Hunterian Museum at Glasgow University in Scotland, where the coin was kept locked in a locker along with three others from the original stack.

Along with other researchers, he examined all four coins under a powerful microscope and confirmed in a paper published in the scientific journal PLOS 1 that there were indeed scratches on the objects and that the patterns were consistent with the coins bouncing inside the wallets.

A chemical analysis also showed that the coins had been buried for hundreds of years, according to Jesper Ericsson, the museum’s coin curator, who worked with Pearson on the project.

Researchers now have to answer the question: Who was Esponsiano?

They believe he was a military commander who was forced to assume the role of emperor of Dacia, the most remote and hard-to-defend province of the Roman empire.

Archaeological research has revealed that Dacia broke away from the rest of the Roman Empire around 260 AD. There was an epidemic, a civil war, and the empire was falling apart.

Surrounded by enemies and cut off from Rome, Esponsian probably assumed supreme command during a time of chaos and civil war, maintaining Dacia’s military and civilian population until it returned to normal between AD 271 and 275, according to Jesper Ericsson.

“Our interpretation is that he is responsible for keeping the military and civilian population in check as they are besieged and completely isolated,” he says.

“They decided to mint their own coins to create a functional economy in the state.”

This theory would explain why the coins were different from those in Rome.

“They may not even know who the real emperor is because there’s an ongoing civil war,” says Pearson.

“But since no real power came from Rome, they needed a high military commander. He took over at a time when leadership was needed.”

After scientists determined the coins were genuine, they alerted researchers at the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu, Transylvania, which is also an Esponsian coin. It was part of the legacy of Baron Samuel von Brukenthal, the Habsburg governor of Transylvania.

Was the baron examining the money when he died? And according to legend, the last thing he did was write a note that said “truth”.

Experts at the Brukenthal Museum, like everyone else, classified the coin as a historical counterfeit. But when they saw the UK survey, they changed their minds.

The discovery is of particular interest to the history of Transylvania and Romania, according to Alexandru Constantin Chitu, acting director of the Brukenthal National Museum.

“If these results are accepted by the scientific community, it will add another important name to our history,” he says.

The coins are on display at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow.

– This text was published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/geral-63741216.

source: Noticias

Mark Jones is a world traveler and journalist for News Rebeat. With a curious mind and a love of adventure, Mark brings a unique perspective to the latest global events and provides in-depth and thought-provoking coverage of the world at large.