Afghan families give medicine to their starving children to calm them down. Others sell their daughters and organs to survive. Millions are on the verge of starvation in the second winter since the Taliban took power again, which resulted in a freeze of foreign aid funds.

“Our children are still crying and not sleeping. We have no food,” said Abdul Wahab.

“Then we go to the pharmacy, buy pills and give them to our kids to calm them down.”

He lives on the outskirts of Herat, the country’s third largest city, in a settlement of thousands of small adobe houses that have grown over the decades, filled with displaced people affected by war and natural disasters.

Abdul is one of a group of more than ten men gathered around us. We asked: How many of them were giving sedatives to their children?

“Many of us, all of us,” they replied.

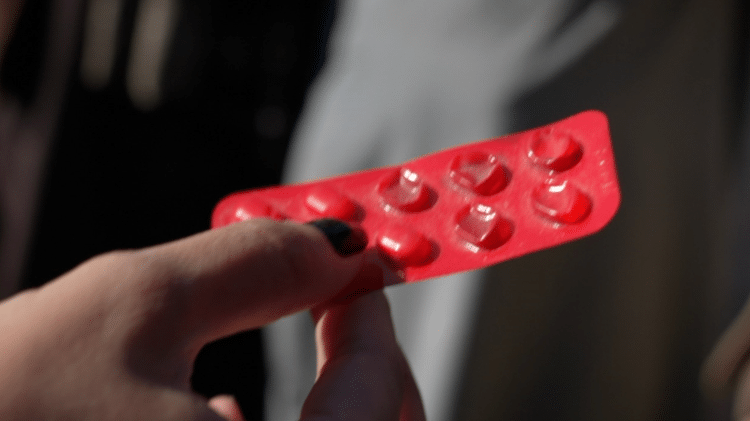

Ghulam Hazrat felt in his tunic pocket and pulled out a pack of pills. These were alprazolam – tranquilizers often prescribed to treat anxiety disorders.

Ghulam has six children. The youngest is one year old. “I’m giving it to him too,” she says.

Others showed us the pills of escitalopram and sertraline given to their children. They are often prescribed to treat depression and anxiety.

Doctors say that when given to young children without proper nutrition, such drugs can cause liver damage, as well as a host of other problems, such as chronic fatigue, sleep disturbances and behavioral disorders.

We found that it was possible to buy five pills of these family-used drugs at a local pharmacy for 10 cents a dollar or the price of a loaf of bread.

Most of the families we interviewed shared a few pieces of bread among themselves each day. One woman told us that they ate dry bread in the morning and soaked it in water at night to hydrate it.

The UN said there was a humanitarian “catastrophe” in Afghanistan.

Most of the men in this region work day jobs in the suburbs of Herat. They have had a difficult life for years.

When the Taliban came to power without being recognized by the international community last August, foreign funds sent to Afghanistan were frozen, triggering an economic collapse that left men without jobs for days.

On the rare days they find work, they earn around 100 Afghans, or just over $1.

Everywhere we went, we saw people forced to take extreme measures to save their families from starvation.

Ammar (not her real name), in her 20s, said she had surgery to remove her kidney three months ago and showed us a scar filled with stitches running from her stomach to her back.

“There was no way out. I heard you could sell a kidney at a local hospital. I went there and told them I was willing. A few weeks later I got a call asking me to come to the hospital,” he said.

“They did some tests, then injected something that made me pass out. I was scared, but I had no choice.”

Ammar claims to have received the equivalent of US$3,100 (about R$17,000) for the kidney. Most of the money was used to pay off the debt to buy food for his family.

“If we eat it one night, we won’t eat it the next night. After selling my kidney, I feel like I’m left unfinished. I’m hopeless. I feel like I’m going to die if life goes on like this.” aforementioned.

The sale of organs in need is not unheard of in Afghanistan. This was happening before the Taliban came back to power.

But even after making such a difficult decision, people still struggle to find ways to survive.

In an empty, cold house we encountered a young mother who said she sold her kidney seven months ago. The family also had to pay off its debts; the money was used to buy a flock of sheep. The animals died in a flood a few years ago and lost their livelihoods.

The equivalent of US$ 2,700 (R$ 14,600) for the kidney is not enough for the family to live.

“Now we are forced to sell our two-year-old daughter. The people we borrowed from say to us every day, ‘Give your daughter if you don’t pay,'” he said.

Her husband said, “I am very ashamed of our situation. Sometimes I think it is better to die than to live like this.”

We hear over and over again about people selling their daughters.

“I sold my five-year-old daughter to 100 thousand Afghans” [cerca de US$ 1.150]”, said Nizamuddin, a member of the congregation. He’s heard from traders that it’s worth less than half a kidney. He bites his lip and his eyes fill with tears.

The dignity with which people lived their lives was broken by famine.

“We understand that this is against Islamic law and we are putting our children’s lives in danger, but there is no other way,” said Abdul Ghafar, one of the leaders of the community.

While playing with her 18-month-old brother Shamshullah in a house, we met Nazia, a pouting four-year-old happy little girl.

“We don’t have money to buy food, so I announced at the local mosque that I wanted to sell my daughter,” said her father, Hazratullah.

Nazia was sold to marry the child of a family in the southern state of Kandahar. She will leave her family at the age of 14, she. So far, Allah has received two payments for him.

Hazratullah took off Shamshullah’s shirt to show us his swollen belly and said, “I used most of them to buy food and some medicine for my youngest son. Look at this, he is malnourished.”

The rapid increase in malnutrition is testament to the impact of hunger on children under five in Afghanistan.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has seen hospitalization rates increase by up to 47% each year at its facilities across the country.

The organization’s nutrition center in Herat is the only well-equipped malnutrition facility serving not only the region, but also the neighboring provinces of Ghor and Badghis, where malnutrition rates have increased by 55% last year.

Since last year, the number of beds had to be increased due to the high number of hospitalizations for children. But despite this, the place is almost always packed. And diseases go beyond malnutrition.

Omid is malnourished and suffers from hernia and sepsis. At 14 months he weighs only 4 kg. Doctors told us that a normal baby at this age would weigh at least 6.6 kg. His mother, Aamna, started vomiting excessively and had to borrow money to go to the hospital.

We asked Hameedullah Mutawakil, spokesperson for the Taliban provincial government in Herat, what measures are being taken to combat hunger.

“The situation is a result of international sanctions against Afghanistan and the freezing of Afghan assets. Our government is trying to determine how many people are in this situation. Many are lying about their conditions to get help,” he said.

He also said that the Taliban are trying to create jobs. “We want to open iron ore mines and a pipeline project.” But there are no signs that this will happen anytime soon.

People have told us they feel abandoned by the government and the international community.

Hunger does not always have immediate visible effects.

Far from the world’s attention, the extent of the crisis in Afghanistan may never come to light.

With news from Imogen Anderson and Malik Mudassir

– This text was published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-63751727.

source: Noticias

Mark Jones is a world traveler and journalist for News Rebeat. With a curious mind and a love of adventure, Mark brings a unique perspective to the latest global events and provides in-depth and thought-provoking coverage of the world at large.