“The only thing worth doing happened after his death.”

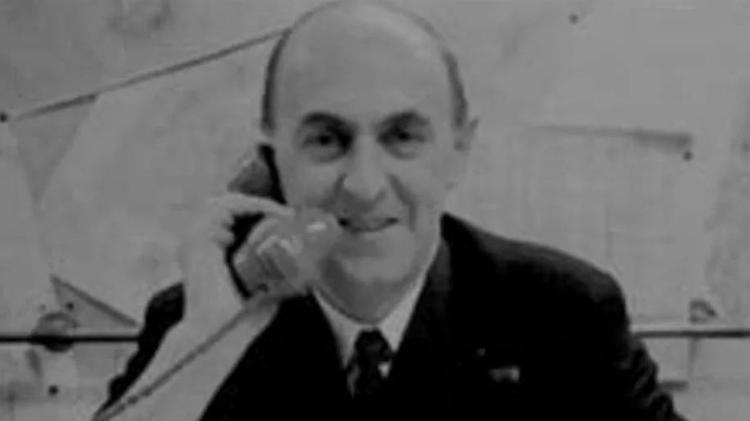

British intelligence officer Ewen Montagu’s view of Welsh Glyndwr Michael may seem harsh.

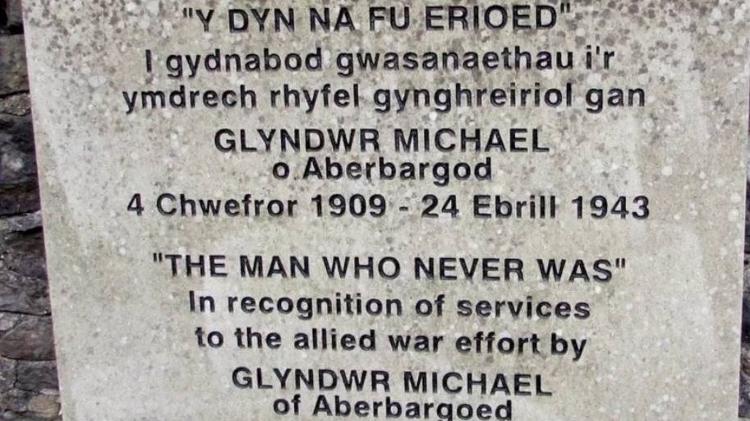

After all, after he died at the age of 34, Michael II.

In April 1943, Welsh’s body was used in “Operation Mincemeat”, considered by British intelligence agents to be the most daring of any conflict.

The British plan managed to deceive the Germans, who redeployed entire regiments from Sicily, Italy to Greece and the Balkans.

Historian Ben Macintyre’s book on deception, “Operation Mincemeat,” is a Warner Bros. made into a movie. In Brazil, the film earned the title “O Soldado que Não Existiu” and will be released by Netflix in May.

“Glyndwr Michael is probably the most unlikely hero of all of WWII,” says Macintyre.

“During the Great Depression of the 1930s, he fled Wales to London to escape extreme poverty. His own father committed suicide after his mining business collapsed.”

The historian explains that Michael’s body was found in a cabin in London’s King’s Cross area and, according to the forensic report, he was poisoned.

However, the historian believes that the act was not suicide.

“I think Michael was so hungry that he must have accidentally eaten poisoned bread,” she points out.

The story befitting of James Bond

Whatever the cause of Glyndwr Michael’s death, his remains were handed over to coroner Bentley Purchase.

The specialist was warned of the need to find a body with injuries similar to those of a plane crash victim, where the parachute did not work as expected.

The body was later transferred to the care of agents Charles Cholmondeley and Ewen Montagu. Thus began the transformation of Glyndwr Michael into Commander William Martin.

The idea of using a corpse to make false plans into enemy territory was first conceived in the 1930s by Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond spy novels.

Fleming, II. During World War II he worked as an assistant to John Godfrey, director of the British Navy’s Naval Intelligence Unit.

In late 1942, the success of the Allies in a campaign in North Africa allowed them to turn their attention to other German-controlled areas in Southern Europe.

Sicily, Italy was the obvious place to start an operation, as domination of the island meant control of ships in the Mediterranean.

The problem was that choosing this location was too obvious.

man who never was

Winston Churchill, the then British Prime Minister, said, “Everyone but a fool knows that the operation will be in Sicily.”

However, this did not prevent the Allies from wanting to take Sicily as a springboard for Italy. For this, they carried out a magnificent act of distraction.

Agents Cholmondeley and Montagu began working on details that would make the deception more believable to the Germans.

They gave the mock officer an extensive identity and history, starting with the choice of the name William Martin, which is relatively common in the British Marine Corps.

They also gave the so-called soldier the rank of captain, which they deemed high enough to carry classified documents, though not important enough to be a familiar face to the enemy.

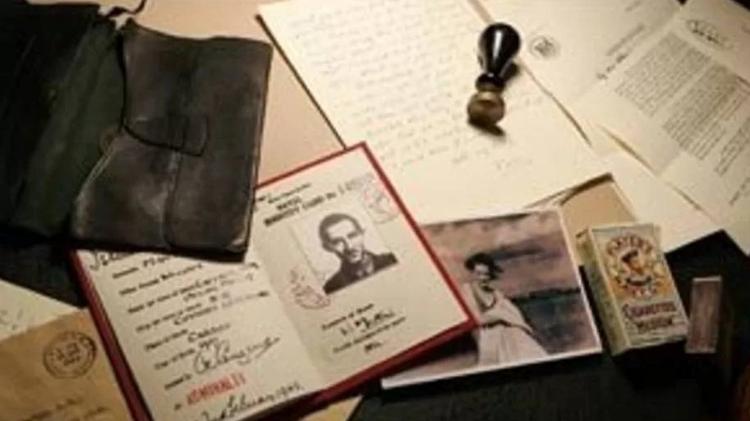

Representatives then chose everyday items that everyone would take with them. In Martin’s case, that meant keys, stamps, cigarettes, matches, a Saint Kitts coin, draft theater tickets, a receipt for a new shirt, a letter from his father, even an overdraft note from the bank.

All documents are written with a special water-proof ink.

Ewan Montagu spent months creating the identity of the fake officer. But Ben Macintyre says the most compelling part of the puzzle is Martin’s fiancee, a young woman named Pam – actually a British intelligence officer named Jean Lesley.

“The level of detail they went into was incredible – they even wore Martin’s so-called uniform and underwear to make it look like properly worn clothes,” the historian explains.

“I was lucky enough to meet ‘Pam’ (Jean Lesley) when I was 80 and she took me across the River Thames to the point where she and ‘William’ were supposedly engaged.

At that time, Montagu’s wife was convinced he was having an affair.”

a big mistake

Cholmondeley and Montagu prepared the body and loaded it into a container filled with dry ice for a trip to Scotland. The vehicle was driven by a pre-war motorsport champion.

A submarine called HMS Seraph was waiting in Scotland. It took 10 days for the vehicle to reach the “delivery point”.

It is worth noting that the crew of the submarine did not know the purpose of the mission. As soon as the officers left Martin’s body in the water, the engines were started, so the current pushed him towards the shores of Spain.

In the early hours of April 30, 1943, a Spanish sardine fisherman found the British officer drowned near the town of Huelva.

German military intelligence was ambushed, and a copy of Martin’s letters describing his plans for an Allied operation in Greece fell on Adolf Hitler’s desk.

At the same time, in a dark basement of the Navy building in London, British intelligence men and women cheered, banging on tables and jumping up and down when the message to Hitler was blocked by Allied military equipment.

One last Wales link

Macintyre says there was another Welsh connection that eventually convinced Hitler that the body was real.

“One of Martin’s father’s letters is thought to have been written from a hotel in Mold (a town in Wales),” says the historian.

“While I was researching my book, I went back to the original hotel record, and the letter actually had Mr. Martin’s name on it at the correct date. The story details are incredible.”

The British admitted an alleged disappointment in a telegram to the Spaniards, being easily captured and demanding that Martin’s suitcase be returned as soon as possible.

“Confidential documents are probably in a black folder,” the cable said.

On July 10, 1943, 38 days after the Allied invasion of Sicily, the island was captured by the Allies. Soon after, all of Italy fell, causing the downfall of Benito Mussolini’s regime.

Glyndwr Michael was buried with full military honors in Huelva.

source: Noticias