[환자 ‘표류’ 해법, 해외에서 찾다]〈2〉 Japan’s ’emergency room hit-and-run’ disappears

Japan, emergency room simultaneous alert network activated if hospital bed cannot be found for more than 30 minutes

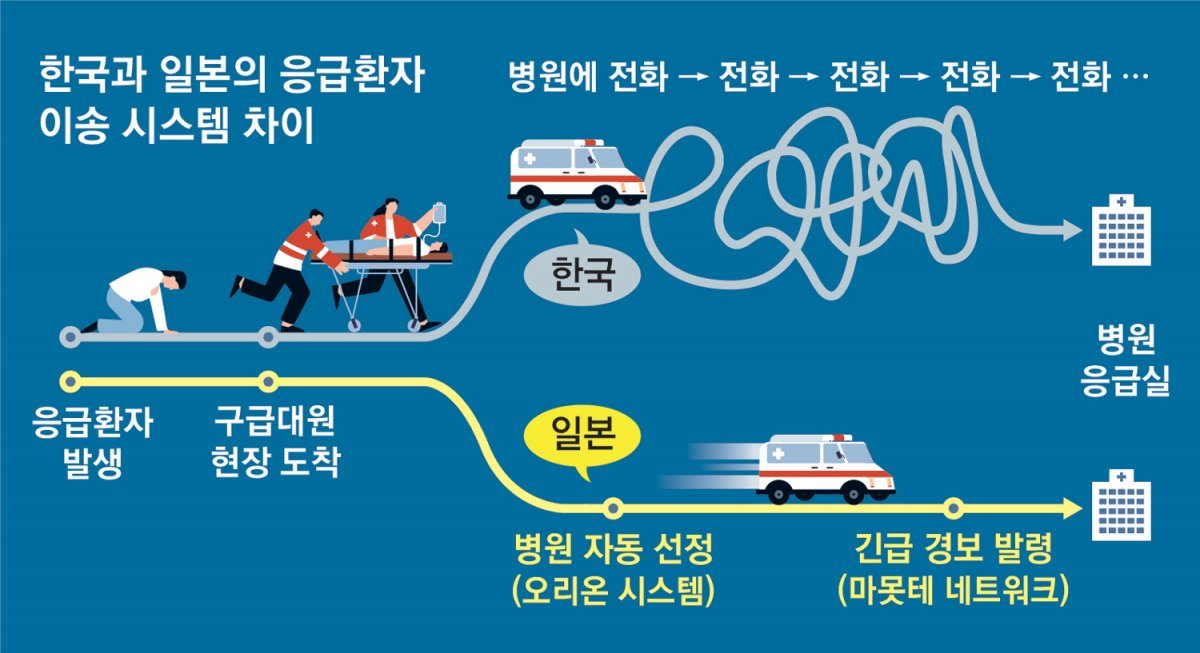

In Korea, paramedics miss golden time by calling each hospital one by one.

‘Gang! Kang! ‘Kang!’

7:20 PM on the 6th of this month. A loud and sharp warning alarm began to sound within the advanced emergency rescue center (emergency room) of the Osaka University Medical School affiliated hospital located in Suita, Osaka Prefecture, Japan. The sound was loud enough that all the medical staff and patients in the emergency room turned around.

This alarm was the sound of an emergency patient in Osaka Prefecture being ‘drifting’ in an ambulance for over 30 minutes without being able to find a hospital to go to. As soon as the alarm sounded, the terminal on the medical staff desk immediately displayed the patient’s main symptoms and vital signs such as blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation entered by the paramedics who had been dispatched to the scene.

Emergency room medical staff entered into this terminal whether to accept the patient based on this information. Only then did the alarm subside. It only took one minute from the alarm sounding for the medical staff to make a decision. Since this was not possible at the Osaka University Medical School affiliated hospital, the patient was transferred to the emergency room of another hospital for treatment.

The name of this system, which sounds an alarm in all emergency rooms of nearby hospitals when an emergency patient is unable to find a hospital and is being driven around by ambulance, is the ‘Marmotte Network’. ‘Marmotte’ means ‘protect’ in Japanese. ‘Currently, the patient is unable to find a hospital to go to. It’s like shouting, ‘Every minute is an urgent situation, so please take this patient to any hospital and save his life.’

This was significantly different from the emergency patient transport process in Korea, where paramedics had to call dozens of hospitals one by one, explain the patient’s condition and inquire whether they would accept the patient. In ‘Drifting, Floating on the Border of Life and Death’ reported by the Dong-A Ilbo Hero Contents team in March of this year, Lee Jun-gyu (13), a patient with cerebral hemorrhage, drifted for 228 minutes without receiving proper treatment after receiving responses from eight hospitals as ‘difficult to accept’. did. Mr. Park Jong-yeol (39), who fractured his leg, lost his leg after wandering for 378 minutes after being notified that 23 hospitals could not accommodate him. The golden time of a patient wandering between life and death is gone while the paramedic is on the phone.

Like Korea, Japan also has a shortage of doctors in essential medical fields. However, the medical staff that the reporter met in Osaka Prefecture from the 11th to the 15th of last month and interviewed via video or email from the 3rd to the 18th of this month agreed that “there are no cases of emergency patients ‘drifting’ in search of hospitals.” Professor Jun Oda of the Department of Emergency Medicine, who heads the hospital’s Advanced Emergency Rescue Center, said, “As we began using technologies such as the Marmotte network to quickly transport emergency patients to the hospital, the number of patients being bounced around in ambulances has almost disappeared. “He said.

Immediately identified in order of distance to transfer hospital

Korea’s essential medical improvement plan announced this month

The ‘ambulance-hospital connection system’ is missing.

On the 13th of last month, Osaka University Medical School Affiliated Hospital Advanced Emergency Rescue Center (Emergency Room). When I entered the emergency intensive care unit where critically ill patients were being treated, I saw a black terminal the size of a tablet PC placed on the staff’s desk. This terminal had ‘Marmotte (まもって) Network’ written on it. Professor Jun Oda of the Department of Emergency Medicine explained, “There is one Marmotte terminal in each emergency intensive care unit and nurse station.”

Paramedics in Osaka Prefecture, Japan, can use the Marmotte network if four hospitals reject their request to accommodate an emergency patient or if they cannot find a hospital for more than 30 minutes. When a paramedic enters the patient’s main symptoms into the Marmotte network, the terminal sounds a loud alarm and displays information about the patient.

After looking at the patient’s information, the hospital presses either the ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ button. The alarm will continue to sound until the hospital presses the button. Shunichiro Nakao, an emergency medicine doctor at this hospital, said, “We never missed a request to accommodate an emergency patient because the alarm rang loudly.”

The Marmotte network, first introduced in 2008, is a system that simultaneously notifies all hospitals in Osaka Prefecture of the presence of emergency patients in a crisis situation such as an ‘ambulance hit and run’. This means that the paramedics ask the hospital ‘one-to-many’ at once whether they can accommodate emergency patients. If you press the accept button at any one of them, the patient can no longer drift away.

On the other hand, in Korea, paramedics inquire ‘one-on-one’ with hospitals about whether a patient can be accommodated. The process of calling the hospital, explaining the patient’s condition, and asking whether or not to accept the patient is repeated until a hospital that accepts the patient is found. Meanwhile, the golden time for emergency patients continues to pass. Moreover, it is difficult for Korean paramedics to immediately recognize the constantly changing emergency room situation. Even if Hospital A, which was notified that it was ‘difficult to accommodate’, has the capacity to receive patients while the paramedics are making calls to other hospitals one after another, you will not know that fact until you call Hospital A again.

Osaka Prefecture also has a system that allows paramedics to quickly decide which hospital to transfer a patient to before ringing the marmotte network.

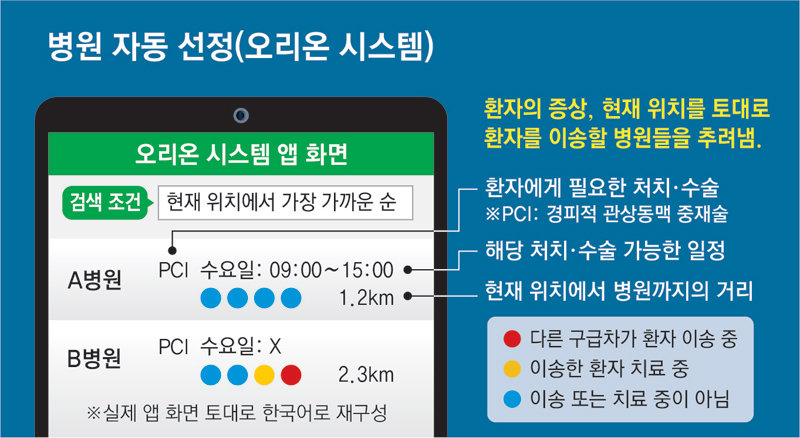

“When you enter the patient’s symptoms, a list of hospitals will automatically appear in order of the closest distance from your current location.” On the 12th of last month, Professor Kentaro Kazino of the Department of Emergency Medicine, who met at the Advanced Emergency Rescue Center of Kansai University Medical School Affiliated Hospital in Hirakata, Osaka Prefecture, Japan, introduced an application (app) used by paramedics. This is ORION (Osaka emergency information Research Intelligent Operation Network system), which was introduced in 2013.

When you turn on this app, a screen appears where you can enter the patient’s gender, age, and main symptoms. If a patient complains of chest pain, enter information such as history of heart disease and difficulty breathing. Once the input was completed, a list of hospitals that could be transferred based on the patient’s symptoms, information, and current location appeared in order of distance. Based on this information, the paramedics called the hospital to check whether they could accommodate the patient.

The process of paramedics deciding which hospital to transfer a patient to is automatic. On the other hand, in Korea, this process takes place ‘in the head’ of the paramedic. The paramedics directly select the hospital to call based on the location of each hospital and the medical departments that can be treated at each hospital, which they are familiar with in advance.

Why isn’t this system used in Korea, where information technology (IT) is more developed than Japan? Even in the essential medical innovation strategy announced by the government on the 19th of this month, there is no information about a system that can quickly connect ambulances and hospitals.

Attempts were made to introduce a system similar to the Marmotte network in Korea, but it was never implemented. The emergency medical system improvement consultative body operated in 2019 discussed a plan where, if two hospitals refuse to allow paramedics to transport a patient, the city/provincial 119 general situation room sends a request for accommodation to a nearby emergency room via group messenger. If there was no emergency room willing to accept the patient, a plan to transfer the patient to the largest emergency room in the region was also discussed. However, the medical community was concerned about the indiscriminate transfer of firefighters, and the fire department was concerned about linking patient information in real time with hospitals to protect personal information, so it was eventually omitted from the final report.

It is not that we lack the ability to develop a system like Orion. Song Gyeong-jun, public vice director of Boramae Hospital (emergency medicine professor), said, “Computers are much better than people at selecting a list of hospitals to transfer to,” and added, “It’s not difficult to create the algorithm.”

In fact, since June of this year, Chungcheongbuk-do has been developing and operating a ‘smart emergency medical system’, an automated system similar to the Orion system, as a project supported by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Kim Sang-cheol, professor of emergency medicine at Chungbuk National University Hospital and head of the Chungbuk Smart City Challenge project, said, “Active cooperation between the hospital and fire departments is most important during the patient transport stage,” adding, “There is also sufficient financial support from the government and local governments to build the system.” “Only then will the participation of private hospitals increase,” he emphasized.

※ This article was supported by the Press Promotion Fund raised through government advertising fees.

Osaka = Special reporting team

| Special reporting team |

| ▽ ▽Reporters Ji-woon Lee, So-young Kim, and Moon-soo Lee (Ministry of Policy and Society) |

Source: Donga

Mark Jones is a world traveler and journalist for News Rebeat. With a curious mind and a love of adventure, Mark brings a unique perspective to the latest global events and provides in-depth and thought-provoking coverage of the world at large.