The tomb of the ancient Egyptian King Tutankhamun in Luxor is one of the most famous discoveries in modern archaeology.

A new exhibition at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of British Egyptologist Howard Carter and his team.

“Tutankhamun: Digging the Archives” exhibition (Tutankhamun: Digging the Archives) stunningly illuminated images captured by photographer Harry Burton include letters, plans, drawings and journals from the Carter archive.

The material sheds new light on the decade-long history of excavation. Was the tomb found largely intact? This was very rare for an ancient Egyptian archaeological site.

The exhibition also challenges the perception of Carter as a “lone hero” and highlights the contribution of many talented Egyptian workers who are often overlooked.

An unnamed Egyptian boy wears a heavily jeweled necklace from a coffin inside Tutankhamun’s tomb, uniting ancient and modern Egypt. Several people later claimed to be children, including Hussein Abd al-Rassul from Gurna, who helped Carter’s team – but none of the allegations were confirmed.

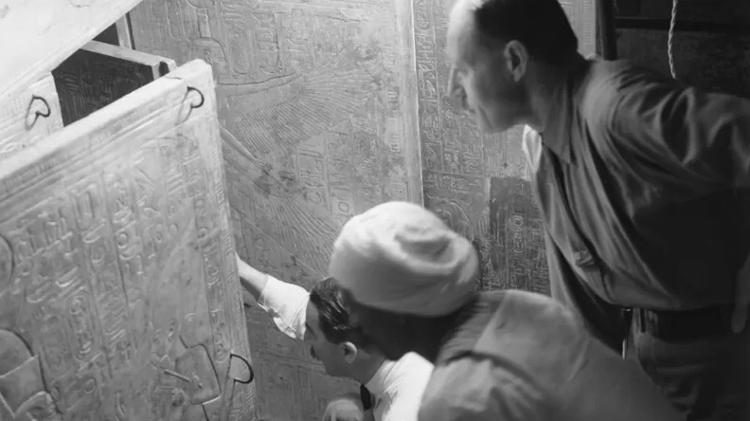

This photograph is among a series that occupies the center of the exhibition. It shows two foremen and a boy carefully dismantling a partition wall to open the burial chamber.

Four Egyptian workers – Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said – were selected and thanked by Carter in their publication. However, it is not possible to identify them among the workers depicted.

More than 50 local workers were hired by Carter, and dozens of other workers, including children, were present at the site, says archaeologist Daniela Rosenow, curator of the exhibit.

Although their names have not been recorded, Rosenow says the images challenge the colonial stereotype of a one-man expedition.

“Through these photos we can see the vital contribution. [dos egípcios] And that makes it clear that what we have here is just part of the story.”

A dramatic, deliberately exposed image shows Carter’s crew opening the doors of a golden bunker. Carter is crouched, his assistant Arthur Callender and an unidentified Egyptian standing over him.

The image helped publicize the discovery of the tomb worldwide and promoted Carter as an “English adventurer”.

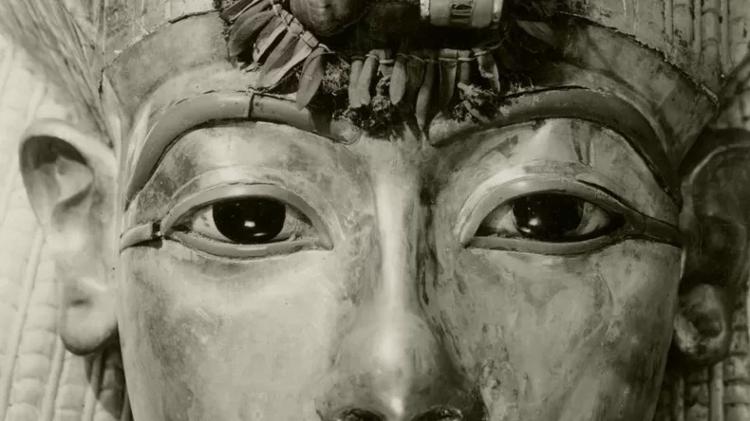

Another photograph of the Burton of Tutankhamun’s outer coffin focuses on the wreath of flowers and olive leaves adorning the young king’s forehead.

Shortly after the exhibition, the natural materials accompanying the mummy were disintegrated. Its existence is preserved only thanks to this striking image.

In another photo, British surgeon Douglas Derry makes the first incision on Tutankhamun’s mummified body during a “scientific study” that began on November 11, 1925.

Egyptian surgeon Saleh Bey Hamdi is to the right of Derry. Pierre Lacau, French Director General of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities; Carter and an Egyptian official are in the audience.

The solid gold mask found on Tutankhamun’s mummified body was one of the most iconic objects discovered in the tomb.

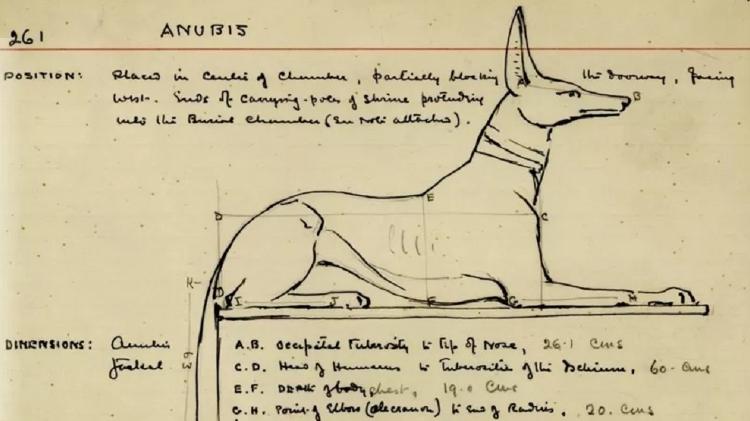

A statue of Anubis, the jackal god of the dead, is the subject of a Carter drawing with notes and measures. The son of an illustrator, Carter trained as an artist before moving on to archeology – but never achieved a formal academic qualification in the field.

Carter named a warehouse located east of the burial chamber “Treasure.” In one photograph, Burton deliberately uses concealed lighting to create a mysterious and dramatic effect by highlighting the sanctuary of the god Anubis.

source: Noticias