“Hell”, “horror” … the testimonies of Canadian soldiers returning from the front, like the war in Ukraine, are almost unanimous. Returning to the country after voluntarily giving a hand to the Ukrainian forces, they returned ill from their stay. But could it be otherwise? Not really, believe the veterans who have been involved in major major conflicts over the past 30 years, who believe that no one can adequately prepare for the experience of armed conflict.

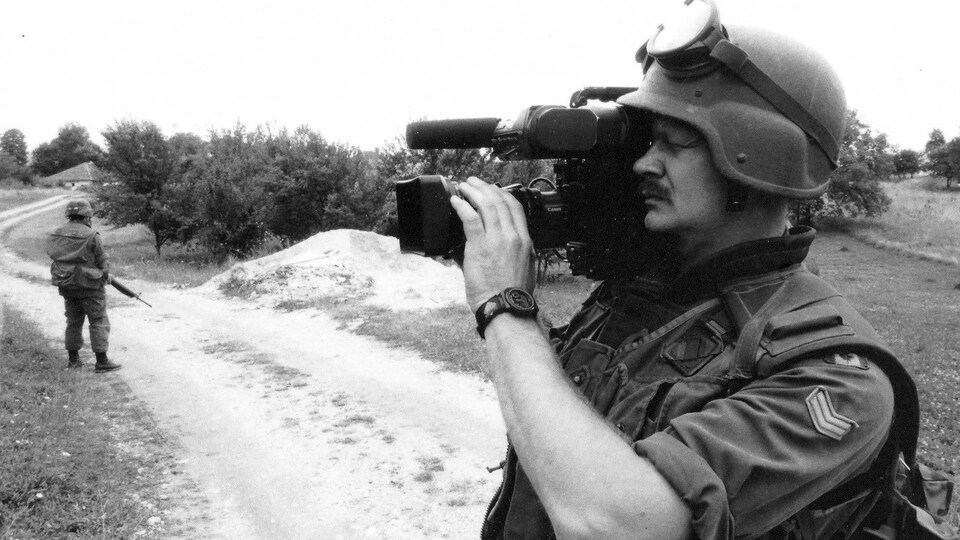

Retired master corporal Marc Bergeron had permanent scars from his overseas missions when he was a member of the Canadian Armed Forces. The resident of Saint-Vallier-de-Bellechasse, in the Chaudière-Appalaches region, signed up in 1984 to live from his passion: photography.

At the time, he recalls, Canadian soldiers were not directly involved in armed conflict. Their duty was instead concentrated on peacekeeping or surveillance missions at one of the two Canadian military bases located in Germany during the Cold War. It’s fun to take risks and get a job, because in the old days, we didn’t expect to go to war. It is not uncommon for Canada to participate in the war other than participating in peacekeeping missions in Cyprushe pointed out.

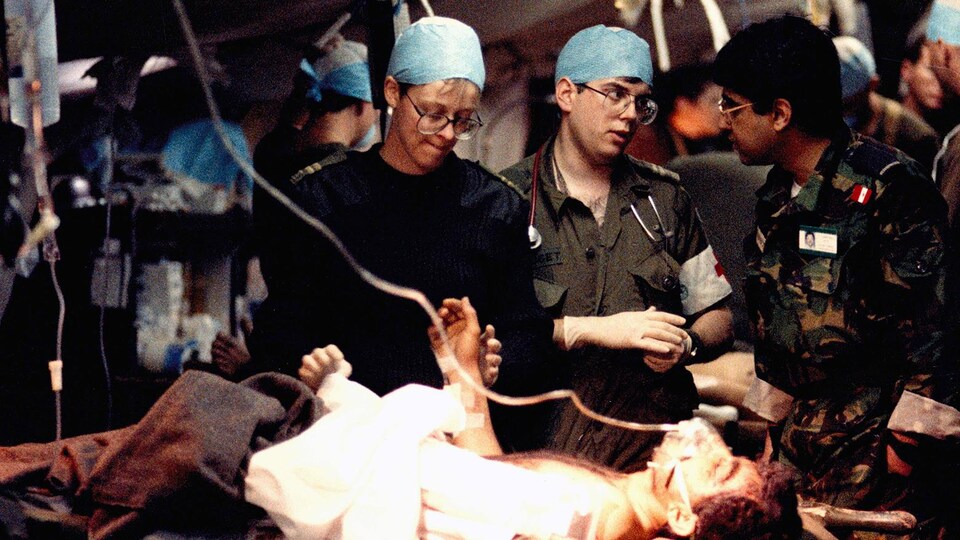

Things changed, however, at the turn of the 1990s, with the outbreak of the Gulf War. For the first time, Corporal Bergeron was called to join the coalition of countries that would liberate Kuwait from the Iraq invasion. He first followed an intensive training course of several weeks in the basics of war. Let’s go through the armament, first aid, the geopolitical plan. What kind of weapon [les Irakiens] will be used, bacteriological warfare. This is unceasing. When you finish that course, you are more nervous because you know it will pay off. This is no longer a joke. This is no longer an exercise.

Using a camera, a camera and of course the weapons of battle, his duty is to document the war from all angles. He sees all colors. The worst you can think of. Everything is a discovery. We didn’t know we were going to film shovels, amputations, wounded dying on the table, dead. […] We also didn’t know we were going to shoot Iraqi prisoners of war.

” It was an awakening to war. You don’t expect what you see. I don’t think you can prepare anyone for this. “

Unable to prepare at all

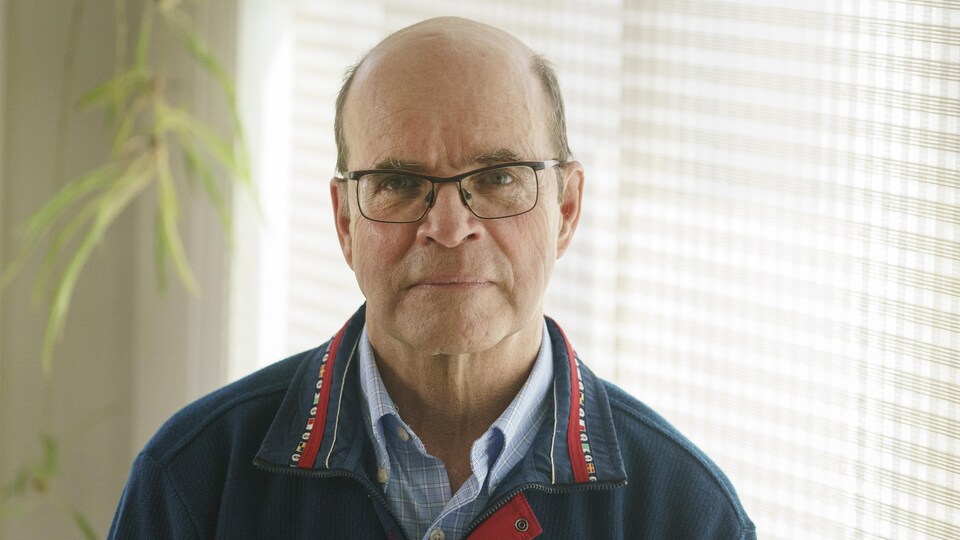

In fact, it is difficult to properly prepare a soldier to actually experience what will happen on earth, says Rémi Landry, a retired lieutenant-colonel. Pre-exercises are important, but no simulation can honestly reproduce reality, he believes, he who saw his share of atrocities during a mission to the Balkans in the 1990s.

Training ensured that I was able to react properly when I was shot and bombed. [Mais] the side that is harder to prepare for is exactly how individuals will react to the atrocities they have to witness.

” I, when I was in Bosnia, […] It was my biggest fear to know if I had reacted enough. “

Guy Marchessault, president of the Royal Canadian Legion in Sherbrooke, speaks regularly with former soldiers who have had post-traumatic symptoms (PTSD). The former Fusiliers de Sherbrooke soldier believes we cannot guarantee that all soldiers will face pure violence properly.

[Le militaire] seeing things that a person normally does not see. This is an attack on his moral values. A person cannot stay for weeks and months in hypervigilance. You can’t always be on pure adrenaline for a long time and there are no consequenceshe believes.

Marc Bergeron, someone knows about it. Horrors, he filmed some and he was also scared for his life. During the war in Iraq, he thought it was his time that he had to take refuge in a bunker while a missile. Scud The Iraqi went straight to his group.

” At the same time, there is the signalman who counts the effect of Scud that falls on us: effect in 20 seconds, 19, 18, 17. Imagine what that feeling was like! Hold your heart so it doesn’t come out of your ear. Scary. [Tu es sûr] that you will die. “

Fortunately, the missile still fell, but the experience was traumatic for Marc Bergeron. Hell doesn’t stop there. For three months, he was immersed in an apocalyptic atmosphere.

Dark in the sunlight [à cause de la fumée dégagée par] the oil wells, which the Iraqis had already started burning. The Americans, who had started fighting on the ground, detonated bombs to destroy the mines. You can’t sleep there. It’s impossible. You look at the night sky and you can just see the planes going up to Iraq. [C’est] a war that didn’t last long, but was still pretty brutalhe recalled.

The master corporal again faced this brutality a few years later, during another mission, this time to Bosnia, where he was even taken by the Serbian army for 16 days and kept in difficult conditions. conditions of detention. When you are first told you will go home, but in a body bagIt starts badly.

” When you lose your dignity as a person, you remember it for the rest of your life. “

Jean-Pierre Gaudreau from Sherbrooke, career soldier, has spent his working life in the maintenance and repair of aircraft engines and helicopter gunships 16 years in the Canadian Forces and 27 years in US Army.

Although his work was mainly done on military bases, he also returned very notably. During the war in Afghanistan, he emphasized regular bathing in a morbid environment. Every day, helicopters arrive with the wounded or dead. […] You see the atrocities.

Long -term consequences

Consequences, Marc Bergeron must still learn to live with them now, even though he has not been in the Forces for 20 years. In his case, the first post-traumatic symptoms appeared almost on the day of a year after his mission to the Persian Gulf. He was sent on many missions, though the symptoms associated with war wounds were exacerbated, year after year.

” The biggest symptom was a major depression that lasted a year and a half. To isolate myself from my house, having drawn curtains, alcohol, alcohol, alcohol, drugs and two suicide attempts. “

He is now undergoing medical treatment, sometimes stumbling and getting up. He must learn to live with these images in his head. Will he still join the Forces if he has to do it again ?. No, certainly nothe answered spontaneously.

Jean-Pierre Gaudreau also has wounds from his military experience. He lost friends and he also evokes the memory of former comrades in the arm that the war changed. The army trains us all the time for all kinds of business to go into battle. But when you come out of the army, you are not deprogrammed by the army. He is not giving you a lesson [t’aider à faire la transition à la vie civile]he moaned.

These traumas are not new, but the help has nevertheless improved over the years. If we go back to World War II, there was no intervention when these people returned. These people are self -medicated. At that time the legions were full. The man would go in there, he would get a lot of big beers and sleep. That’s his treatment.

We shouldn’t think that everyone returns with operational stress injuries, he says. There are some who can afford to live with that and continue their military careers afterwards..

Lieutenant-Colonel Rémi Landry, who is also an associate professor at Sherbrooke University, is nonetheless categorical: the face of war is an eternal scar. He himself experienced the effects of post-traumatic stress on his return from a mission in the former Yugoslavia.

We can prepare people, we can tell them that yes there will be difficulties […] [mais] there are some images that will haunt you for the rest of your lifehe concludes.

Source: Radio-Canada