For the first time in Colombian history, an outsider leftist favorite to win the presidency. This is a turning point for a trend that has been excluded from the political system for years.

“Colombia has never had a left-wing president.”

This is one of the most heard words in the campaign for the presidential election to be held on Sunday this year (29/5). Gustavo Petro Urrego, a candidate from the left, is the favorite in every poll.

Colombia has had progressive leaders in the past, but a popular politician has never reached the presidency without the support of the established traditional parties.

And Petro, a shy ex-guerrilla who grew up in small towns, may be the first president to have an economic agenda that criticizes the capitalist model at work in the country.

Colombia has never been led by revolutionaries like Mexico or Bolivia, popular movements like Peronism in Argentina, or a socialist like Salvador Allende in Chile.

Left reformist politicians approaching power were killed. And their murders unleashed waves of violence.

Although the country has had one of the most stable democracy and economy in Latin America for decades, a growing portion of the population has developed a discontent with the ruling class, which it blames for repeated armed conflicts and one of the most unequal societies in the world. world.

After two moments of social turmoil in 2019 and 2021, a pandemic that has exacerbated poverty and inequality, and a right-wing government that recorded the highest number of disapprovals in recent history, the population is fed up with everything. And the left wants to take advantage of that.

But why has it been so difficult for the left to come to power in Colombia until now?

persecuted and secret

Let us first briefly review the history of the Colombian left.

Although there were socialist expressions in a 19th century full of civil wars, Mauricio Archila, a historian who specializes in this subject, argues that social movements could only be talked about with a left agenda in the 1930s.

The so-called “Banana Tree Massacre”, which occurred in the United States in 1928 during the strike of the United Fruit Company workers, foreshadowed what was to come.

Within the traditional bipartisan structure, unlike the Conservatives, the Liberal Party represented left-related demands. However, the distance between the base and the leaders, which belonged to the urban aristocracy, almost always prevented the consolidation of truly popular proposals.

In the 1930s and 1940s Colombia had the most progressive president in history: Alfonso López Pumarejo of the Liberal Party, who made room for unions in government and laid the foundation for agrarian reform.

After the financial crisis of 1929, his project, inspired by the American New Deal, was called Revolution in Motion. But the revolution never came.

The Right reacted immediately, the Liberal Party split, and in the end, private ownership, the rise of the communists, and the fear of “leaping into the void” prevailed.

In this context, the first peak of violence took place. The villagers were persecuted by paramilitary groups called “birds”.

Image: Getty Images

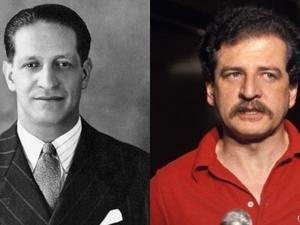

In the 1940s, popular figures such as Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina and Getúlio Vargas in Brazil ruled neighboring countries. In Colombia, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán emerged as a charismatic orator, the son of a teacher and a bookseller, made a career in the Liberal Party but was always labeled a dissident.

On April 9, 1948, when a major popular movement brought him to the presidency, he was assassinated (today unknown by whom) and another wave of violence was unleashed.

A more chaotic situation was rectified as a power pact alternated between the two traditional parties signed in 1958. The National Front was formed, which brought some stability and excluded any outsider movement from the system.

At the height of the Cuban revolution, thousands of Colombians took up arms against what they saw as the “perfect dictatorship.” Six guerrillas emerged, but none of them succeeded in overthrowing power.

Some laid down their arms and formed political parties, but their leaders and militants were persecuted and killed. The most cited case classified as “genocide” belongs to the Patriotic Union: 5,733 militants were killed between 1984 and 2016, according to official data. Among them are two presidential candidates: Jaime Pardo Leal and Bernardo Jaramillo Ossa.

The National Front ended in the 1970s, but its logic remained, and subsequent governments did not make drastic changes to maintain political and economic calm.

Democratizing projects such as the 1991 Constitution were carried out, and many peace processes were signed with the guerrillas that widened the political spectrum. A foreigner from the rural elite also came to power in 2002, Álvaro Uribe, who broke the two-party system.

In practice, however, the ruling class did not undergo radical changes. In fact, it went even further to the right.

A new surge in violence between 1995 and 2012 made it impossible to discuss reforms. Presidents were elected for their positions on rural warfare. The persecution of trade union, peasant and student movements continued. Any progressive agenda, if any, was lost.

Since 2005, the democratic left has created a structure outside the Liberal Party, which has been supporting the right for decades. A key figure in this process, Petro is the result of twenty years of work.

A “guerrilla” or split left

The first reason to explain the endless crisis of the Colombian left is that having a progressive agenda in the midst of the guerrillas is a huge disadvantage, to say the least.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 and the consolidation of capitalism as the dominant model, all leftists in the region received a prestige blow.

But unlike other countries in the region, insurgency has been and continues to exist in Colombia for many years. Since the 1990s, its growing proximity to the drug trade and symbolic attacks that have killed thousands of civilians have eroded its popularity.

M19, to which Petro was a member and was demobilized in 1989, received 12% and 30% of the vote in two elections (presidential candidate Carlos Pizarro was assassinated in 1990), FARC, which signed peace in 2016, support more than 1% from the electorate not to take

“The petitions of the guerrillas may be the platform of a party or union, but because they are armed they have radicalized themselves and de-legitimized that agenda,” explains Gonzalo Sánchez, a historian specializing in conflicts.

“In such a closed country, any democratic demand has become destructive,” he adds.

The guerrilla movement has not only affected the discourse and reputation of the political left, but also its own formation, which has never been freed from divisions and dogmas.

right answer

According to experts, a second reason for the weakness of the left is the strength of the right.

Since the 19th century, the conservative establishment had a patronage-based political and social structure that allowed it to remain in power.

“The Church’s influence over the State and the education system has created an Armed Force with no autonomy and no renewal, and an Armed Force dependent on traditional parties, and an electoral system that supports abstention, an authoritarian matrix that remains in power without too much counterweight.” Emma Wills.

Between 1949 and 1991, the Siege State, a constitutional mechanism that gave extraordinary powers to the president, remained in force for a total of 30 years in different periods. That is, 70% of the time.

Fear of the so-called communist threat so dangerous for Colombia’s main ally, the United States? Wills notes that many of his academic works have been translated into decrees and criminal regimes that limit social and political rights to leftist movements.

However, the state also engaged in illegal practices to stop the rebellion and any leftist movement.

Dozens of investigations, some conducted by the state, have proven that paramilitarism, the armed movement that perished the most during the conflict, arose in part thanks to its alliance with the regional and military elites.

Leopoldo Fergusson, an economist who studies the conflict, found that the victory of left-wing leaders in local elections between 1988 and 2014 statistically led to an increase in paramilitary violence in these areas.

“It’s a reaction of the traditional elite to compensate for the increased access by foreigners to official political power,” says the Economist.

culturally conservative

Abstention votes have always been high in Colombia. There are millions of people who have refused to participate in the electoral system for decades.

This is why priest and human rights activist Javier Giraldo calls Colombia a “genocidal democracy”.

However, the ruling class often prides itself on having one of the most stable democracies in the region. Because there were no revolutions and socialisms, and there were no authoritarian regimes that restricted the vote.

Colombians who voted almost always chose their organizational name.

According to experts, this is due to the fact that Colombian culture was very conservative, at least until the end of the 20th century.

They attribute this to three things: a cautious economy without major jumps in consumption, growth or openness; The influence of the Church, which declared itself secular until 1991, on education and the State; and the absence of emigration.

“Colombia modernized and opened up to the world too late, and this allowed the authoritarian matrix to have a huge impact on culture,” says Wills.

In a sea of informality, the Colombian job market allied with the oligarchic power structure, Sánchez says the only way to socialize is through illegality.

“If previously the only way to rise socially in Colombia was to marry someone from the oligarchy, it’s been violence and drug trafficking that has given access to a more cosmopolitan life over the last 40 years,” says the historian.

But everything is changing. Regions have been articulated, the country has been connected to the world in part through migration inherited from violence, and peace agreements have opened the way for a new range of interests in social and cultural issues.

Also, over the last 20 years, the left has slowly and painfully managed to unify and build up a certain electoral base.

Gustavo Petro has been one of the main architects of this electoral restructuring since his time in Congress. He is now the favorite to be president.

The story causes many to consider the possibility of a new murder or coup d’etat. Others believe that many years have passed: that Colombia, the country the left never ruled, has changed.

source: Noticias