My memories of the day I learned that my father Tahir Ahmed had been murdered are vivid but incomplete.

I remember the room, but I don’t remember who was there. It was Friday but I don’t remember the time. I remember hearing the landline phone ring, but I don’t remember who in my family answered it.

It was my brother who called. “They found it. He was killed.”

I don’t know who repeated my brother’s words, but at that moment the life I knew was over.

My mother immediately burst into tears. We sat in silence in amazement when we heard that my father’s body had been found in a septic tank at Rajshahi University in Bangladesh, where he worked as a professor in the geology and mining department.

Our entire extended family had gathered at my brother’s home in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. He was not with us. The day before, he had driven six hours to Rajshahi, near the Indian border, to look for our father.

My family suddenly started talking, they interrupted each other.

Aspect? Because? Who would want to kill him?

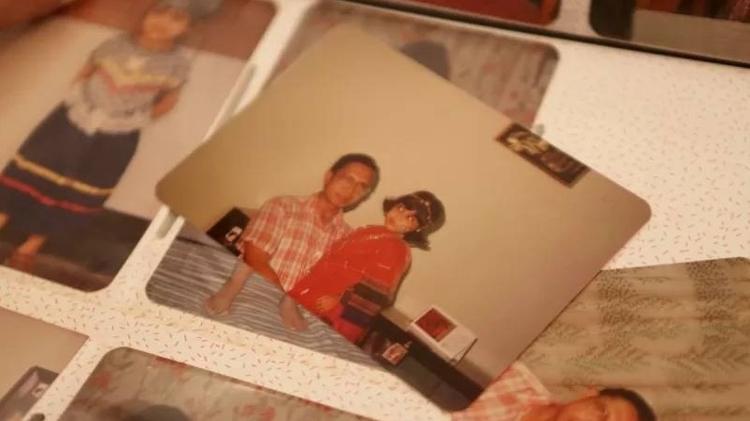

My father, a modest academic who would rather walk or take public transport than buy a flashy car, a college professor whose students his students seem fond of, a husband who was involved in grocery shopping and cooking when it was still rare in Bangladesh, my father who always held his hand as I crossed the street at 18. .. Who would want this man dead?

This question would only be the beginning of our family’s nightmare.

Two days ago, on Wednesday, February 1, 2006, my father took a bus from Dhaka to Rajshahi University.

He loved the bustling, lively campus that was our family home when I was younger. We lived in a small house on campus provided by the university and everything we needed was close by.

My brother Sanzid and I would walk to school in the mornings and spend the night on the playground with the kids of other university professors. We knew everyone on campus. It was a happy and safe balloon for us.

But one day, Sanzid and I dropped out of school and moved to Dhaka. Sanzid started working in the human resources department of a large multinational company.

I studied law at university on the advice of my father, who made incredible prophecies of what would happen to him. I had no intention of becoming a practicing lawyer. After graduation, I thought maybe I would join an international non-governmental organization or become an academician.

But even then my father seemed to know what would be best for the family. I entered university in 2006 and my mother came to live with me in Dhaka, where I settled.

The week he died, my father had come to visit all of us in Dhaka for a few days and arrived in Rajshahi in the early afternoon on Wednesday, February 1, 2006. She called and rang my mom to let her know she was okay there. again a few hours later, just before 9 o’clock.

I think he was getting ready for bed. Police would later find his pants hanging on his bedroom doorknob.

After that, he would only survive for a short time. The coroner later said he was killed before 10 pm.

My father had returned to the university for a meeting on the future of a colleague, Mia Mohammad Mohiuddin. She was a close family friend, but her relationship with my father had abruptly ended not long ago.

My father had discovered several cases of plagiarism in Mohiuddin’s work and brought the matter up to the faculty at the university. A meeting was scheduled to discuss how the episode would handle the debate.

But my father neither attended that meeting nor answered our calls. The watchman, Jahangir Alam, said, interestingly, that he was not at home and did not see it coming.

Alarmed, my mother asked my brother to go to Rajshahi that night to call my father. The next day, February 3, 2006, my brother found my father’s lifeless body in a septic tank in the garden of the university’s residence. The investigation was now for murder.

For a moment, the eyes of the world were on my family. My father’s death made headlines, a murder mystery, a real-life detective novel. His face shone on television and was printed in the newspapers. Local and international press went after the hideous details that could make the story compelling. After all, good, popular, healthy men don’t die that way.

There were many unanswered questions. Who would kill a respectable college professor? Was it personal resentment? Islamic radicals? What has history said about Bangladeshi society?

In the midst of the pandemic, I took care of my brother and my mother. They acted quickly.

My mom went to meet my brother in Rajshahi to help the police set up a timeline and check all suspects. Within weeks, four more people were arrested and charged, including Mia Mohammad Mohiuddin (my father’s colleague accused of plagiarism), Jahangir Alam, the caretaker of the university dormitory, and Alam’s brother and sister-in-law. murder. from my father.

During the trial, Jahangir Alam and his relatives testified that Mohiuddin persuaded them to kill my father and promised him money, computers and a job at the university. Muhiddin denied the allegations.

In 2008, four of the men were found guilty by the Rajshahi court of first instance and sentenced to death. Two people were acquitted. I should have been there but I wasn’t. The four men appealed and the case was taken to the Bangladesh High Court.

My mother and brother worked tirelessly to ensure justice for my father. But I felt useless.

At the time of the lower court hearing, I was a little over a teenager. My family had protected me all my life, and even after my father died, they insisted that my sole focus be on finishing college. They supported me financially and morally.

I continued my education, trying to concentrate on my law books, but I was still unsure of what to do with my life. Until 2011, when my father’s murder case came to the Supreme Court.

The court released Mia Mohammad Mohiuddin on bail and she was released pending trial. He had hired more than 10 lawyers, and his defense would obviously be detailed.

Suddenly my future made sense. I knew what I could do with my life. I can use my diploma to help the prosecutor’s case against my father’s killers.

My position was unique, I was part of many different worlds. I can cooperate with my family and translate documents into legal jargon for them. I knew the police, I knew my father, and I even knew two of the defendants. I can be an intermediary in this process that brings justice to my father.

I graduated from law school in 2012 and immediately started helping lawyers in the law firm. Bangladesh doesn’t have many female lawyers working in criminal cases, but everyone saw my worth and welcome to the team. It was where I spent all my waking hours. I turned down other cases just to focus on my dad.

In 2013, the Supreme Court passed a decision upholding the death sentences for Mia Mohammad Mohiuddin (colleague my father accused of plagiarism) and janitor Jahangir Alam. However, the death sentences of the other two men who were relatives of Alam were commuted to life imprisonment. The judge decided they had helped, but Mohiuddin and Alam were the architects of my father’s death.

But the process isn’t over yet.

The guard and his relatives had confessed to my father’s murder and all claimed they had been approached and paid by Mohiuddin. Mohiuddin’s lawyers, however, filed a new appeal, this time to the Bangladesh High Court’s Appellate Division, the country’s highest appellate court.

I reviewed documents, drafted documents, created timelines, profiled criminals, talked to lawyers, and nurtured the souls of my brother and mother. Endless nights, weekends, a few Ramadans were spent praying and keeping in mind our goal, justice and peace for our father.

I was now a committed lawyer on a mission in my thirties, and no longer the nervous teenage girl who had her world shattered in 2006. But we’re stuck with the courtroom schedule. We waited eight years for the appeal to be heard.

Mia Mohiuddin is a wealthy man with good connections. Her brother-in-law is an influential Bangladeshi politician.

He had resources and a large team of lawyers. These lawyers argued that he had nothing to do with my father’s death, that they had always been close friends with him, and that there was no physical evidence against him, only circumstantial evidence.

It didn’t matter if the other three men made detailed confessions or if their behavior after the crime wasn’t quite as expected from someone close to our family. Mohiuddin, who visited us often years ago, stayed away from my father’s funeral – he was the only faculty member who did not attend. Nor did he visit our family to offer support.

With many cases pending trial, the Supreme Court only took my father’s case up at the end of 2021. And by April 5, 2022, judges led by Judge Hassan Foez Siddique concluded that Mia was on trial. Mohammad Mohiuddin was guilty of my father’s murder and they upheld his death sentence.

After the hearing, I released a statement on behalf of the family saying we were happy with the decision, but I’m not sure “happy” is the right word. I still don’t have the words to describe what our family has been through over the past 16 years. Pain is unthinkable. Sometimes I wonder if I can find peace knowing that my father died this way.

The struggle to bring justice to my father dominated my adult life to the point where my own life was suspended. People ask me if I’m going to settle down and have a family of my own.

Maybe after my father’s killers died. Maybe then I can feel it’s over. My father was my world. He was a very good, decent, simple and wise man.

What the assassins did to my father is unthinkable, as Mohiuddin is in danger of losing his job. But for him, I will carry on, fight for justice and live a good life.

source: Noticias