London In addition to all its state surveillance and prosecution apparatus, China is adopting a new tactic as it escalates the crackdown on the press: using citizens to discredit information published by foreign journalists and even Chinese journalists working abroad for western tools. country.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that organizations affiliated with the Chinese state began to harass foreign media professionals publicly, resulting in massive online and face-to-face harassment campaigns.

As part of this new tactic, state media and popular citizens on the social network Weibo are posting the names and photos of foreign journalists who “promote and attack China”, describing their reporting as “biased” or “dishonest” and threatening them.

Foreign journalists have data and locations exposed in China

China is a notorious censor of the country’s media, as the government controls almost all content published in any media outlet. Finally Global Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF)The country was ranked 175th in a rating of 180 countries.

According to CPJ’s annual prison census, The country is also the country that arrests the most journalists in the world.. But the work of foreign correspondents, which escaped the pressure of the Chinese media for being broadcast abroad, has historically been more difficult for authorities to silence.

But CPJ says it has begun harassing foreign journalists online as the country has become more sensitive to its image abroad amid accusations that it has mishandled the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sophie Beach said, “Taking out foreign journalists is part of a broader strategy to control all information, including online voices. Chinese Digital Timesto the committee.

But it’s also part of a strategy to rewrite the global narrative about China, particularly its role in dealing with COVID.”

Spamuffing is Part of China’s Twitter Press

Attacks don’t just happen on Chinese networks. An analysis by researchers Danielle Cave and Albert Zhang from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), quoted on the Axios website, says that a campaign of attacks on female journalists working in Western outlets was conducted through a network of Twitter accounts called “Spamouflage.” associated with the Chinese state.

According to Axios, the attacks were acknowledged by Twitter, which says it has suspended more than 400 accounts for policy violations. The Chinese government has denied any involvement in the accounts.

Pressure in China threatens foreign media work

CPJ’s China correspondent, journalist Iris Hsu, drew attention to how hostility towards foreign media professionals increased as the government’s crackdown on the press increased.

For CPJ, this response is directly linked to the criticism the country has received since the outbreak of the coronavirus.

As an example, Hsu cited attacks by international journalists who traveled to the city of Zhengzhou, Henan Province, in July 2021 to report on a major flood. There, residents accused them of “spreading rumors” and “destroying containment”. [imagem da] Chinese”.

The Chinese Foreign Correspondents Association reported that many also received abusive messages and intimidating calls on social media containing serious threats.

read it too

China ‘wins favor’ over QAnon backed by fake news from Russia on war, study says

According to CPJ, this harassment of foreign journalists or journalists working for the international media was encouraged by the Henan Communist Youth League, an official subordinate organization of the Communist Party of China, which considers the international news coverage of the floods to be “humiliating”.

The league urged its followers on its Weibo platform to discover the whereabouts of BBC reporter Robin Brant.

Confirming the party’s “accusations”, China’s Foreign Ministry accused Brant of “falsifying the true state of the Chinese government’s efforts to organize rescues and the courage of local people to save themselves, and implying attacks full of ideological prejudices against the Chinese government”. and double standards.”

Sophie Beach, operations and communications manager Chinese Digital TimesThe US-based organization that archives and translates censored internet content from China says online censorship and harassment has increased since the new national security law.

“National attacks on people deemed critical of China have been going on for years, in different forms, against journalists, human rights activists, and others.

But in recent years, online attacks seem to have become more frequent and more prominent.”

read it too

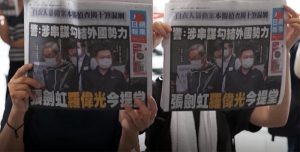

Hong Kong continues to put pressure on the press with the arrest of one of its best-known journalists

Chinese pressure hit American journalist

Another victim of online stalking was Emily Feng, a reporter for NPR (US public broadcaster) in Beijing. He traveled to Liuzhou, a city in southern China’s Guanxi Autonomous Prefecture, to write about the Chinese delicacy “luosifen” or snail noodles.

During his visit to investigate the story, he was followed by authorities, who tried to prevent Feng from telling a story that was supposed to be “fun”, the journalist told Twitter.

After the report was published earlier this year, online harassment began: Feng was tagged as “anti-Chinese foreign citizen of Chinese descent” by posts on Weibo and Chinese news sites.

CPJ describes how his words were twisted to manipulate the Chinese population:

“One website in particular, the state-funded College Daily, appears to have deliberately distorted Feng’s words. The foreign media journalist once again digs up the ‘dirt in China’: Luosifen will cause another covid pandemic’ headline followed by an article with a mistranslation.

Feng described snail noodles in his NPR article as “another snack that could keep China in quarantine for another year,” but College Daily turned it into a snack that “could keep China in quarantine for another year.”

read it too

Hong Kong’s free journalism ‘undermined’ by pro-Beijing state media

The same publication continued to attack the NPR journalist with screenshots of the two reports.

“Almost all of the articles he’s published on NPR were geared towards China. You can tell he couldn’t say anything good from the headlines alone.” College DailyUsing shoddy and misleading translations of Feng’s reports.

In one example, the original title “China excels at the Paralympics, but its citizens with disabilities fight for more opportunities” translated as “China excels at the Paralympics, but its citizens with disabilities still struggle to get into the Games Paralympics”.

Attacks on Asian-American Journalists Outside of China

CPJ’s attack on NPR journalist College Daily It also represents a growing trend in Chinese propaganda targeting reporters of East Asian descent whose independent reporting is perceived by the authorities as a betrayal of their roots and homeland.

Sophie Beach details:

“Chinese journalists are called ‘racial traitors’ if they report anything less than flattering about China.

The worst attacks seem to be against women of Chinese descent, because nationalism always has a strong misogynistic tide.”

But in CPJ’s view, the narrative by Chinese-born journalists that the media and Western governments serve as political tools to defeat China may have “sinister uses” that could discredit their work as well as raise fears that they could face legal prosecution in the future. country.

The organization’s survey cites a case that occurred in December 2021 as an example.

State propaganda tabloid Global TimesHe described the Chinese-born visual investigative reporter Muyi Xiao, an offshoot of the state-run newspaper The People’s Daily. New York Times, As an example of a professional using the Western media to “ambush his friends and his homeland from behind”.

The article stated that Xiao’s curriculum includes working with the Magnum Foundation, ChinaFile, and other groups. The newspaper described some of these NGO organizations as “anti-Chinese” and accused Xiao of “lying to his heart” or “acting like a convert” in his dealings with them.

“By associating Xiao with foreign NGOs, the state may be laying the groundwork for filing the Overseas Non-Governmental Organizations Activities Management Act, which prohibits Chinese citizens from ‘engaging in temporary activities in mainland China’ and ‘acting as intermediaries’ to foreign NGOs.

Those found guilty of stealing, secretly collecting, buying or illegally giving away state secrets may face five to 10 years in prison.”

We Olympic Games inside Beijing Winter 2022, office boss from the Washington Postt Chinese, US-born Taiwanese Lily Kuo has received a lot of backlash on Twitter. A story about the mocking mascot Bing Dwen Dwen, who had to return Your tweets are temporarily private.

However, the journalist reported that the attacks continued via e-mail. One of the messages calls him ugly, stupid, says his shit-filled head needs to be destroyed and ends with “go to hell”.

To stop what seems like a never-ending steam of abuse after a Bing Dwen Dwen story, I blocked a bunch of accounts and protected my tweets today. Now they email me their insults! This really made me laugh. pic.twitter.com/YJWbkQsN0n

– Lily Kuo (@lilkuo) February 11, 2022

Reporters who are not Chinese citizens face less risk, but are not immune to Chinese pressures.

CPJ recalled the case of the BBC’s Beijing correspondent, John Sudworth. In March 2021, he left China, where he had been for nine years, due to threats of surveillance, obstruction, intimidation and legal action against him and his staff.

Sudworth became the target of online propaganda campaigns after reporting on the origins of Covid-19, re-education camps and forced labor in Xinjiang’s cotton industry.

At a news conference after Sudworth left the country last year, State Department spokesperson Hua Chunying told foreign reporters: “There is a price to be paid for those who spread rumors and defamation.”

The committee notes that of the 50 journalists arrested during CPJ’s 2021 census, only two are international reporters – meaning some relief for professionals of other nationalities working in the country.

read it too

source: Noticias

[author_name]