The epic journey to the tomb of Saint James at the northwest tip of Spain is very popular. It has intrigued and captivated people for centuries.

Hundreds of thousands of travelers and pilgrims come here from far and wide every year, but I am not one of them. Instead of the deep valleys that curve into churches, I have another, entirely different goal: a strange and desolate place called Pheasant Island.

While searching for illustrated maps of the West Pyrenees while trying to better understand the Spanish Basque Country, I came across this strip of land under one hectare. On the Bidasoa River (near the mouth of the Bay of Biscay), between the border towns of Hendaye, France and Irun, Spain.

The intriguing Pheasant Island is administered by each of the neighboring nations on a semi-annual basis. This is a historical record of the rivalry between the two countries.

Border irregularities can be found throughout Europe and in other parts of the world. But a 200-metre-long island that changes country twice a year is something extremely strange. And interestingly, very few people know about Pheasant Island.

history everywhere

I learned about this mysterious island before I came to see it up close. I was with Pía Alkain Sorondo, an archaeologist who organizes walking tours of the area. Like most people in this part of Spain, he feels compelled to keep the stories of the Basque Country alive, no matter how unusual.

“I love telling the story of our heritage,” Sorondo says as we walk along the Franco-Spanish border east of San Sebastián. In a way, we are going back in time.

We’ve left behind a few industrial districts, apartment buildings, and pintxos bars, a Basque Country snack served with bread. Before us are the archaeological remains of an old bridge built by the Romans and the island itself.

“History is hidden by this river, but most people walk around here without knowing anything. That’s what I’m trying to change,” he says.

When we arrived at our destination (a park in front of the island, by the river), we were met with a special sight. The elliptical and tree-covered Pheasant Island is just 10 meters from the Spanish side of the river and 20 meters from the French side.

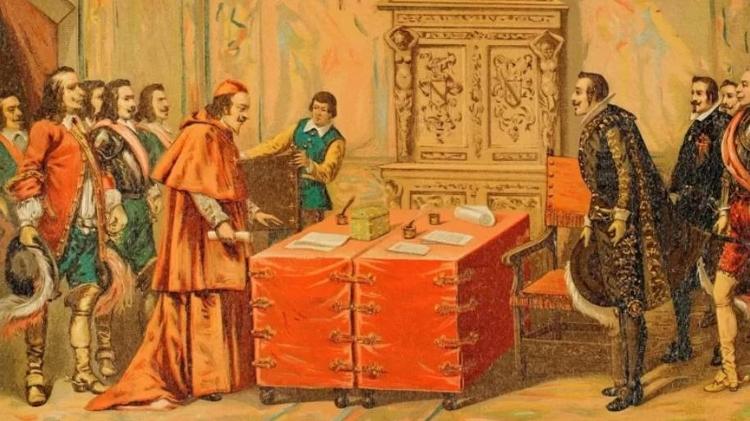

Its historical significance is so great that it is rarely open to visitors. In the center is a huge monument resembling an inscribed tombstone. It gives an idea of the weight of the centuries-old history of the place. The majestic monument celebrates the meeting in 1659 at which the Treaty of the Pyrenees was negotiated, which sealed the peace between Spain and France.

“Learning the history behind this place is like a discovery,” says Sorondo. “Almost a ghost island.”

Many different names have been given to Pheasant Island throughout history. For starters, the current name – Isla de los Faisans in Spanish, Faisai Uhartea in Basque or Île des Faisans in French – is a mistake.

“There are no pheasants on Pheasant Island,” the French novelist Victor Hugo complained while visiting it in 1843. Indeed, there are only wild ducks with green crests and migratory birds.

In Roman times, the island was known as “Pausoa”, a Basque word meaning “gate” or “passage”. The French translated it as “Paysans” (peasants) and later became “Faisans” (pheasants). Over time, the name Ilha dos Pheasões remained.

The humble island finally came to prominence in 1648 after the armistice between France and Spain at the end of the Thirty Years’ War. It was chosen as a neutral area to mark the new borders between the two countries.

A total of 24 summits with military escorts were held in case the talks failed. Only 11 years later the peace treaty, called the Pyrenees Treaty, was signed.

On this occasion, a royal wedding was held. King of France XIV in 1660. Louis IV, King of Spain, at the place where the peace declaration was made. He married Philip’s daughter, Maria Theresa.

Wooden bridges were built to ease the passage, and the royals arrived in government chariots and boats.

Rugs and tables were commissioned. Diego Velázquez, IV. At Philip’s court, the painter and author of the masterpiece As Meninas (a portrait of King Philip’s another daughter, Margarita Teresa, with her bridesmaids) was responsible for organizing most of the festivities.

Pheasant Island has become so symbolic as a metaphor for peace that the two countries have agreed to joint custody of the area. Spain would be responsible from February 1 to July 31, and France would take responsibility for the remaining six months of each year.

At that moment, the world’s smallest condominium appeared.

Condominium in international law

By definition, condominiums are places determined by the existence of more than one sovereign state. The term is derived from the Latin condominium: “com” means “set” and “dominium” means “property right”.

Over the centuries, several countries have been embroiled in geographic disputes over condominium. Governments have spent decades debating the details of who owns what and for what reason. Typically, condominiums are experimental geopolitical appendages, not centers of empires.

Currently, there are eight types of condominiums worldwide. These include Lake Constance, a triple condominium between Austria, Germany and Switzerland; In addition to the Brčko county and the disputed territory of the Republic of Serbia, both in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There is also the Joint Regime Territory, a maritime territory shared by Colombia and Jamaica, and the Abyei region claimed by Sudan and South Sudan.

The Mosel River and its tributaries Sauer and Our form a shared river condominium between Germany and Luxembourg. Bay of Fonseca is a triple condominium between Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Finally, Antarctica is the largest and most important condominium, theoretically continental, administered by 29 signatories of the Antarctic Treaty, which has consultative status.

The day I visited Pheasant Island, the area was under Spanish rule. A group of people explored the corners of the island by boat and only one person on land stopped to take pictures.

Other than managing the garden, protecting the boat dock, discussing fishing rights, and monitoring the water quality, the Spaniards don’t have much to do.

Visitors are allowed on the island on rare occasions, such as the biennial power handover days, when the island is filled with official ceremonies, flags, delegates, diplomats, and all official trappings; or the occasional private tour to visit the local heritage.

But an alarming phenomenon that resonates among border communities is the number of immigrants trying to cross the river illegally from Spain to France. The day before I arrived, a foreign national drowned while trying to swim across the river. While Sorondo and I were talking about the history and politics of the Basque Country, a police boat was searching the waters for the body.

On the Spanish side, current figures from the Irun-based NGO Irungo Harrera Sarea estimate that as many as 30 migrants arrive every day from the north seeking safe passage into France.

As a tidal channel, the Bidasoa River has a brutal height difference of 3 to 4 meters, flowing back and forth across the official border on the national road bridge as a direct attack.

“This is still a place of renewed hope for many people,” Sorondo says, “but it’s also a death trap.”

As these hurtful words hang in the air, a single thought crosses my mind as I leave the room.

Pheasant Island may be a forgotten historical footnote. However, in our nuanced and unpredictable world of border disputes and land grabs, it is a symbol of peace that must always be remembered.

This report was originally published at https://bbc.in/3Bb52D6.

source: Noticias

[author_name]