Let’s start with a quick test.

You are lost in a big store that looks like a maze and you don’t know how to get out of it. Who do you want help from?

Question 2: You are writing a policy document to advise the US government on how to manage its national borders. Where do you look for advice?

Last question: You need to draw a map of the cosmic web, how do you do that?

Of course, there are several answers to these questions, but in any case, you can be inspired by one organism: slimy mold, which also goes by many different names.

Being scientifically correct isn’t exactly a pattern… but at least one of its kind is extraordinary.

“Mold is part of the fungal world, but slime mold is actually a protist (not an animal, plant, or fungus)—essentially a giant cell,” says biologist Merlin Sheldrake, author of the book. mixed lifeWhat topic does it cover?

Slime mold is a plasmodium, that is, a cell containing many nuclei. So, unlike most single-celled organisms, you don’t need a microscope to see it.

And this single cell can weave vast scouting webs of vein-like tentacles that can stretch up to a meter long.

star among all

There are about 900 species of slimy mold, but let’s focus on Physarum Polycephalum, which literally means “many-headed mold.” Also known as the “blob” (referring to the classic 1958 movie). bubble).

Why are the world’s scientists so excited about this particular species?

“It’s become an iconic problem-solving organism. It’s easy to grow and fast growing, which is one of the reasons it’s been so well studied,” explains Sheldrake.

“But above all, his behavior is extraordinary.”

He can do all kinds of things.

“Explore, solve problems, adapt to new situations, decide between alternative courses of action – and it’s all brainless!”

How does he do this?

“Physarum is sensitive to chemical gradient, so it can grow towards chemical signals or stay away from unattractive ones.”

“First, it tends to grow in all directions at once. Then when it finds food, it pulls back and creates connections between food sources.”

It’s like you’re in a bit of a desert and need to look for water. You have to choose only one direction to walk.

Physarum Polycephalum can “walk” in all directions at once until it finds food; Then, through a series of chemical contractions, it shrinks the branches that find nothing and strengthens those that do.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all that they can use these contractions to do this kind of analog computation, to integrate information without the need for a brain. Their coordination doesn’t happen everywhere at the same time and in one particular place.”

A rail network in Japan

All this means that the “blob” is capable, in human terms, of solving problems, creating networks, navigating systems, and mazes with incredible efficiency.

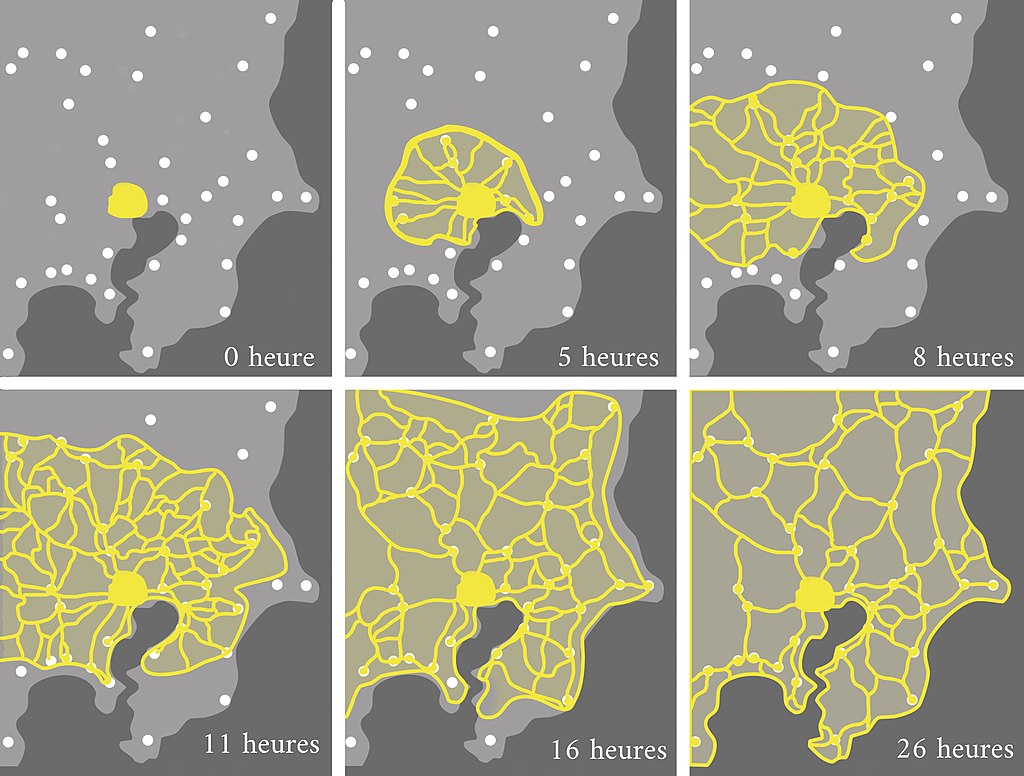

There’s an iconic Japanese study from 2010 where Physarum charted the Greater Tokyo rail network, and all it took was a small Petri dish and a handful of oats.

Studies show that Physarum loves oatmeal, it’s their favorite food.

“So they modeled the Greater Tokyo area by putting oat containers in city centers and then launched it. In a matter of hours, they created an efficient network connecting the oat containers together, and this network was very similar to the subway network. Available in the greater Tokyo area,” the study details.

In a matter of hours, Physarum had built an effective network that took decades to build in real life.

Tim Tim / Wikipedia

Adapted from an example from Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki’s work on the creation and optimization of networks by P. polycephalum.

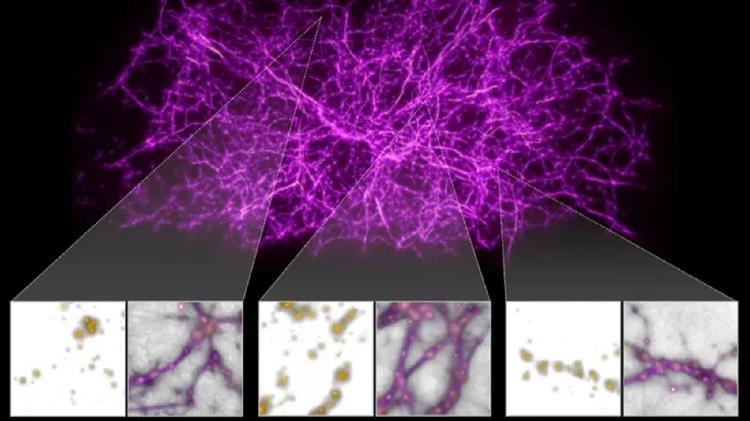

“blob” in the universe

After the Tokyo study, experiments began around the world with Physarum Polycephalum to design new urban transport networks or find effective fire evacuation routes, or even map the cosmic web… it sounds strange, but it happened.

A team of scientists ran a digital simulation tracking the locations of 37,000 known galaxies.

Thus, a drop-inspired algorithm adapted to work in three dimensions from Petri dishes was released in a virtual feast where galaxies are represented, so to speak, by stacks of digital oatmeal cups.

From there, the algorithm visualized the largely invisible threads of matter that astrophysicists believe connect the galaxies of the universe, producing a 3-D digital map of the underlying cosmic web.

They compared this to data from the Hubble Space Telescope, which detects traces of the cosmic web, and found that they all largely matched.

So there seems to be an uncanny similarity between the two webs, the “blob” web created by biological evolution, and the web of structures in the cosmos created by the primitive gravitational force.

academic stains

Let’s go back to the harsh reality of that little blue dot in space that is our world.

Physarum can also help us with problems that go beyond mapping and networking to more complex human things like policy making and governance.

“In a way, Physarum is an economist in terms of getting a big universe,” says experimental philosopher Jonathon Keats.

In 2018, he went to Hampshire College in Massachusetts, USA with an idea.

“With the idea of having a group of these experts on campus to reflect on some of the world’s toughest problems, I suggested that blobs be appointed as visiting professors.”

It was the world’s first academic program for a non-human species and was called the Plasmodium Consortium.

The polycephaly of Physarum became scientists who were entitled to a post.

“They don’t have windows, but the droplets don’t really like light, so from their point of view that was fine and we were able to get started as soon as we got there.”

They modeled human problems in such a way that blobs could “understand” them to gain unbiased perspectives.

“Physarum are super-organisms: although they are many, they are one. Therefore, they are more objective than we are when it comes to human affairs.”

They started with the usual issues of networking and mapping, distribution and transportation, before moving on to some of the larger policy concerns, from “drug policy to issues related to our resource use,” Keats said.

Trump’s Wall

Perhaps the most controversial experiments were those investigating international border politics.

“We’ve created a simplified world, really what everybody does when they create any model (economists do this all the time).”

“What we did was take one of the most basic conditions: One place has something, another place has something, and every place wants to protect what it has against the other.”

They used two primary sources for the blobs, protein and sugar, and spread them in a Petri dish, each on the opposite side, and experimented with a wall between them and without it, and left the Physarum to figure out what to do with it. these resources.

“They not only survived, but also thrived in the absence of a wall and thrived further in the border area,” explains the researcher.

“So we wrote a letter to Kirstjen Nielsen, who was the US Secretary of Homeland Security at the time, and we sent it to the United Nations and many other government agencies as well, telling them that borders are not a good idea and it is not a good idea. We must overcome the fear of realizing that it is helping.”

Absurd?

Of course, these multifaceted international problems cannot be reduced to a few petri dishes.

But the thing is, these experiments are deliberately exaggerated to force us to think in new ways.

“The Plasmodium consortium is kind of ridiculous. People laugh when they hear that the blobs have formed an expert group in collaboration with people at a university in the United States, because that’s not how things work.”

But I think there is something very serious behind it. Physarum has extraordinary intelligence, so we need to combine some of the insights we get from watching how they behave, by thinking about ourselves in ways we haven’t done before.”

That’s the most attractive thing. That a brainless organism can teach us to be more objective, to think more long-term, and to approach a problem in a way that we do not.

And on some puzzles, like mapping the cosmos, he may be faster than us.

All of this calls into question our definitions of human intelligence.

“Our hierarchical view of intelligence with humans at the top of the Great Pyramid reveals the narcissism of our species,” says Sheldrake.

“Thinking about the world without using ourselves as the standard by which all other living things should be judged can help soften some of the hierarchies that underpin modern thought.”

These hierarchies mean: homo sapiensWe have an incredibly high opinion of ourselves, and it has helped us move forward.

But perhaps this has already served its purpose.

“I think we humans need to believe in some kind of superiority. That high self-esteem has been the engine of domination. We’ve been able to do more, and it’s a result of believing we can do more,” says Keats. outside. .

“But we’re reaching a limit to the point where this way of thinking makes the world worse for us and for other species. So it’s time to rethink.”

And the catalyst for this rethinking is Physarum Polycephalum, a one-celled brainless protist at the bottom of that hierarchy where it could shake up the entire system.

* This article is based on the “Slime mold and Problem solving” episode of the BBC series NatureBang. If you want to hear Click here.

– This text was originally published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-62703311.

source: Noticias