Dahir’s brother died of starvation. Now, her two sisters are facing poor health and malnutrition.

BBC reporter Andrew Harding returned to the town of Baidoa to revisit the family, who had to flee the worst drought in Somalia in 40 years, after authorities urged the international community to recognize the food security crisis as a famine emergency.

Warning: This story contains uncensored images.

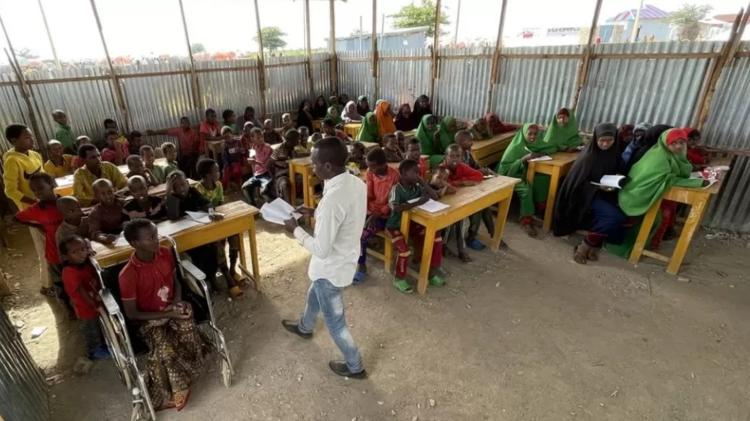

Dahir, 11, is making his way through makeshift cottages on the Baidoa border towards a tin-roofed school near the main road.

Is he wearing the only pants and shirt he owns and holding the other well? a new textbook.

As the school’s sole teacher, 29-year-old Abdullah Ahmed, writes the days of the week on the board in English, Dahir and perhaps 50 of his classmates chant “Saturday, Sunday, Monday…”.

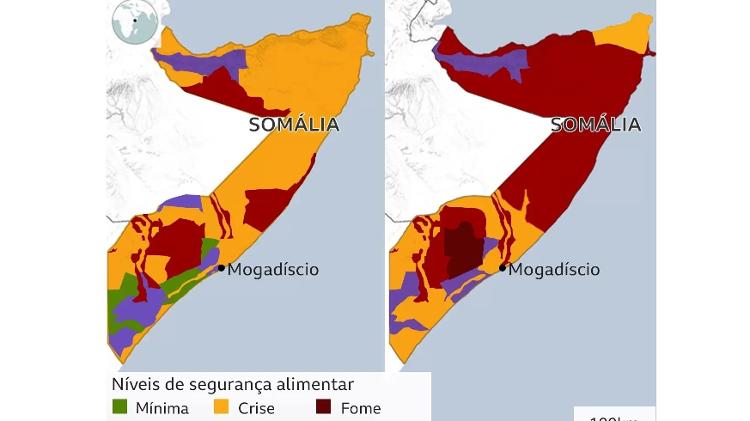

A burst of interest sparks children for a few moments, but soon the yawning and coughing begin again? Signs of famine and disease reverberate like a dreary soundtrack on the plateau of the rocky landscape outside the town of Baidoa, which in recent months has become a haven for hundreds of thousands of people trying to escape the worst drought to hit Somalia in 40 years.

“I think at least 30 of these kids don’t have breakfast. Sometimes they come to me and tell me they’re hungry,” says Ahmed.

“They have a hard time concentrating or even coming to class.”

On our other visit to this part of southern Somalia six weeks ago, Dahir was sitting in tears next to his mother, Fatuma, in the doorway of the family’s ramshackle makeshift cottage.

A few days earlier, his younger brother, Salat, had starved to death after their trip to Baidoa, leaving the countryside severely affected by drought.

Salat was buried a few meters away. Now his tomb is surrounded by huts built by the newcomers.

“I’m worried about my sisters. I wash for them. I wash their faces too,” says Dahir to six-year-old Meryem, who is coughing hoarsely and complaining of a headache, and then four-year-old Malyun, a deep-eyed old man, sitting numb on his mother’s knees.

Fatuma puts his hand on Malyun’s forehead and says, “He’s hot. I think it’s measles. They could both be measles.”

Cases of measles and pneumonia have spread in Baidoa in recent months, killing many young children whose immune systems have been weakened by malnutrition.

At Baidoa state hospital, doctors and nurses move between beds in the intensive care unit, inserting IV lines into babies’ skinny little arms and oxygen probes in their tiny nostrils.

Several children’s limbs were blackened and blistered as a painful response to prolonged starvation, as if they had been caused by severe burns.

“We got a few more supplies [de ajuda humanitária]???????? But it’s still not enough,” says Abdullahi Yusuf, chief physician of the hospital.

“The world is drawing attention to the drought in Somalia right now. We’re seeing visits from international donors. But that doesn’t mean we’re getting enough support. I hope it comes soon. The situation is very dire.”

He described the situation as “terrible” six weeks ago. He notices a slight drop in the number of hospitalizations today, but explains that this is likely due to several days of rain affecting some dirt roads and causing some families to focus on planting plants rather than taking sick children to the hospital. . .

The situation is ‘worsening’

Back at camp, Fatuma carries a plastic gallon of water from a community faucet. Dahir comes out of the hut to help him clean up a battered metal bowl while his sick daughters lie wearily in the hut.

“My son is very helpful. He does a lot to help the girls,” Fatuma says.

While boiling the water, the phone rings. The caller is her husband, 60 years old, Adan Nur, who called from their home in a village within three days’ walking distance in the area controlled by the extremist Islamist group Al Shabab.

“She says she’s planted the millet. It’s okay. She’ll be back soon. But we’ve lost all our animals. We can’t live on crops alone, so I’ll stay here. Our way of life is over,” Fatuma says after she finishes the call.

His decision is backed by the opinions of many experts, who warn that this rainy season is “more unsuccessful” than the last four. By spreading a light touch of green across the desert outside Baidoa, but without any real impact on the crisis.

“It’s still getting worse. Many people come here in search of food, safety and water. And many children die from malnutrition. We object.” [ao governo e à comunidade internacional] As Baidoa Mayor Abdullah Watiin briefly stepped out of a community meeting in a heavily guarded campus, he said they viewed the situation as a famine emergency.

Inside the enclosure, an army general warns locals of the growing threat from the al-Shabaab group and tells residents to be on the lookout for explosive devices and ambushes.

The expectation is that government troops and militias will expand an offensive further north that seems to have had some success but risks making access even harder to some of the drought-affected rural communities.

At the end of the day, does Fatuma house his two sickest daughters? Mary and Malun? on a blanket on the earthen floor of the cottage.

The offer to take the children to the hospital was rejected in favor of treatment with traditional herbal medicine. Thereupon, Fatuma, who is also tired, lies next to the girls.

“I just want them to get well,” Dahir says, watching three of his little blankets and solemnly repeating the phrase two more times.

– This text was published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-63635745.

source: Noticias

Mark Jones is a world traveler and journalist for News Rebeat. With a curious mind and a love of adventure, Mark brings a unique perspective to the latest global events and provides in-depth and thought-provoking coverage of the world at large.