A visit to a minefield begins with basic safety observations that can save lives. After all, you have to be very careful when you are just steps away from deadly buried explosives.

Red stakes on the ground indicate danger. Anyone who continues to walk will run the risk of stepping on a mine.

White stakes are clear and safe road signs. And the black stakes show where an anti-tank mine used to be, whose explosives had already been detonated.

The use of protective equipment is essential. It includes a helmet with a visor that covers your face from ear to ear and just below your chin. The protective suit almost covers the knees, protecting vital organs and arteries from the effects of any accidental explosion.

In the heat of the Lebanese summer, the equipment is overwhelming. Mine clearance specialists begin their work just after sunrise to take advantage of the lower temperatures.

They rest for 10 minutes every hour. When the midday sun reaches its highest point, they are almost done with their daily work. It is very dangerous to work in situations where conditions can lead to loss of concentration. Even a momentary slip can be fatal.

On December 3, 1997 (25 years ago), the Ottawa Agreement, known as the Mine Ban Treaty, was signed, the international treaty banning anti-personnel landmines, considered one of the most successful disarmament treaties in the world. To date, 164 countries have agreed to participate.

Weeks before the treaty was signed, the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work in banning landmines around the world.

The organization has existed in Lebanon since 2001. Mine clearance is a major operation and continues almost every day. This year alone, they will have cleared two million square feet of land and neutralized nearly 10,000 land mines.

Besides dealing with cluster bombs in the Bekaa Valley and improvised explosives (IEDs) that ISIS has left in the northeast of the country, the main job involves clearing mines on the Lebanese-Israeli border.

The so-called Blue Line was drawn by the United Nations in 2000. It was intended to physically mark the withdrawal of Israeli forces from southern Lebanon.

The Blue Line is a high wall in some parts, and a metal grille that allows you to peer through it in others. Beneath the surface lies a 120km minefield designed to create an impassable barrier. About 400,000 land mines were placed there, some about a meter apart.

In the Arab village of Ellouaizi, the barrier that marks the end of Lebanon and the beginning of Israel is at the very end of a mined zone. A meter or two away, behind the gray concrete blocks is an Israeli military tower. The distant hills are shrouded in fog.

This heavily mined land poses a danger to the large numbers of refugees moving from Syria to Lebanon. They want to live on the land and cultivate it, but they don’t know the risks.

Three quarters of the Arab Ellouaizi’s population are Syrian refugees trying to make a living hundreds of kilometers from their homes. This brings out another vital reason to clean up the area besides security.

Agriculture is the main activity in southern Lebanon and farmers are desperate for land to be cleared so they can use the land. Lebanon’s devastating financial crisis, coupled with food shortages caused by the war in Ukraine, means growing crops is an increasingly urgent priority.

Abu Ghassan Awada has a field of peppers grown and ready for harvest. Above them, peach trees grow above our heads.

He remembers the sounds of explosions at night as goats, sheep, and foxes detonate mines. For this reason, he could not cultivate his land for years.

“I was a contract worker for others,” he says. “But now I can hire people to work on my land.”

He still devotes time to the maintenance and repair of the metal grid that marks the boundaries of his farm. Beyond that, a few meters away, the land is still an active minefield. He knows he shouldn’t go there.

Some of MAG’s oldest employees have been part of the team for decades. A large poster with a Lebanese cedar at the door of its headquarters shows their names and faces.

Hiba Ghandour is MAG’s program manager in Lebanon. It is also passionately committed to getting more women to participate in demining efforts in addition to men.

“When I post our job postings, even adding a picture of a woman doing the job helps us reach everyone,” she explains.

One such woman is Suaad Hoteit. She started working four years ago and even met her fiancee while working in the minefield. She deftly removes her helmet from her head and tells she about her day at work.

“I get my detector, I go out into the field, and I start searching,” he says. “When I find a mine, I call my supervisor to check it out. And at the end of the day I blow it up.”

I was surprised that he could speak so impartially on such a dangerous subject.

“It’s been four years so it’s a daily routine,” she smiles. “My first year here I was really scared. Now I understand the danger. I work here because I want to show people that women can do anything. We are strong and independent.”

Landmines of the kind Hoteit is looking for still injure and kill many people in 60 different countries. There are about 15 deaths per day in the world.

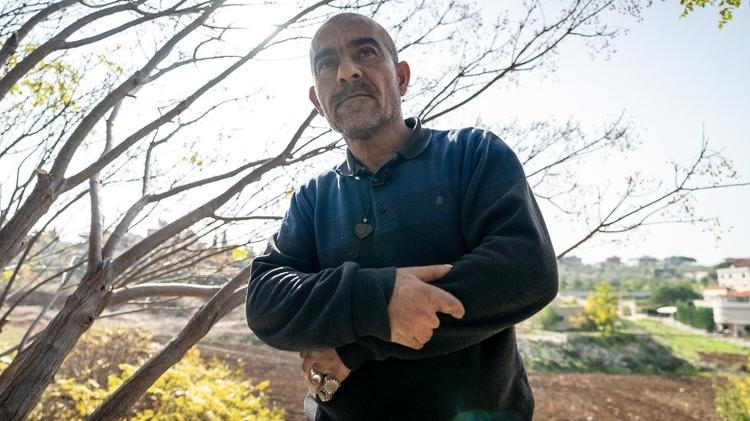

Haidar Maarouf Haidar was one of these people. He wears a special white elastic brace on his right hand. Haidar carefully lifts the coffee table as he remembers the day a landmine exploded while planting a tree in his garden. Even though it was two years ago, that moment is still fresh in your memory.

“Suddenly something exploded and I heard a dreamlike sound,” he says. “I didn’t know what it was. I bent down for a moment and then something happened. I was unconscious and couldn’t see my fingers when I woke up. They were gone.”

Haidar turns his hand to show what’s left of his fingers—just four logs sticking out of his palm.

“My psychological state has changed, that was the first thing,” he continues. “I worked every day, doing everything with my hands, crushing rocks, burning wood with them. My body was active.”

“Now if I use my hands, it’s like there’s an electric current. I’m having trouble walking because of my leg injury. My life has completely changed. Now I can’t do anything but raise my children.” Haydar says.

international aid

After all this suffering, Lebanon is at least close to the finish line. As the Arab Ellouaizi gathers in the minefield, MAG’s Hiba Ghandour wants to show us how far they’ve come.

“We’ve cleared 80% of the contaminated land in Lebanon. We just need to keep moving forward and it’s the support of our international donors that made this possible,” he says.

Countries such as the United States, France, Norway, the Netherlands and Japan are at the forefront of landmine clearance financing. Help is important, but the amount of money offered is dwindling. In Lebanon alone, it fell from US$19.7 million (approx. R$103.8 million) in 2019 to a forecast of US$12.1 million (approx. R$63.8 million) in 2023.

It is difficult to predict how long it will take to clear the remaining 20% of Lebanese minefields. The change in available funds is one of the reasons. But new technologies also have a big impact on the estimated time frame.

Last year, a new rubble crusher significantly accelerated the mine disposal process. It rips the soil and hidden devices apart before detonating it. Sometimes they are detonated inside the machine and the thick shield contains the explosion.

The machine does not replace decommissioning specialists as they can only operate on level ground. But it definitely makes work go faster.

Some of the larger bombs – anti-tank mines – are also handled in a special and innovative way. Mine clearance teams are now so close to the politically sensitive border between Lebanon and Israel that detonating large mines could damage the border. This would not be good for the fragile relations between the two countries.

Therefore, special termite sticks are introduced into mines that are still in the soil, where they accumulate. The intense heat ignites explosives without creating a massive explosion.

With wild flames in front of him, Mohammed caresses the fresh grass sprouts that cover his Atris land. For decades the land was useless, full of mines. It was impossible to even walk on it.

“I was sad, depressed, and angry,” she says. “I can’t describe the feeling of not being able to use the land we grew up on without being mined and planting there became impossible. It was horrible.”

The vegetables he grew were planted six weeks ago – just 24 hours after the land was declared cleared and returned to him.

“I couldn’t wait. We thank everyone for your efforts who made this happen,” says Atris.

As she crouches to pick up her new crop, she gently pulls roots out of the ground and shines with a radiant smile on her face.

– This text was published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-64112812.

source: Noticias

Mark Jones is a world traveler and journalist for News Rebeat. With a curious mind and a love of adventure, Mark brings a unique perspective to the latest global events and provides in-depth and thought-provoking coverage of the world at large.