Ukrainian farmers have 20 million tons of grain that they cannot take to international markets, and a new harvest is about to begin.

As prices rise around the world, what can be done to get food to people in desperate need?

In early February, Nadiya Stetsiuk was expecting a profitable year. In 2021 the weather was fine and his small farm in central Ukraine’s Cherkasy region had an abundance of corn, wheat and sunflower seeds.

Prices in the international market were high and rising every day, so he stocked up on some to sell later. But Russia invaded Ukraine.

His territory hasn’t seen the worst of the war – like 80 percent of the country’s farmland is still under Ukrainian control – but the impact on his farm has been profound.

“We haven’t been able to sell grain since the invasion. The price here is now half the price before the war,” says Stetsiuk.

There may be a food crisis in Europe and the world, but there is a bottleneck here because we cannot get this food out,” he said.

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba described Russia’s offer to lift the blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports as “blackmail” in exchange for lifting sanctions.

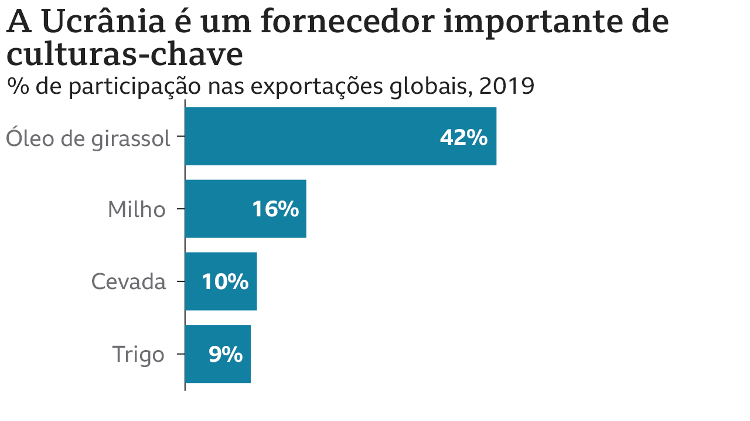

Ukraine is surprising as a food exporter, contributing 42% of sunflower oil, 16% of corn and 9% of wheat traded on the global market.

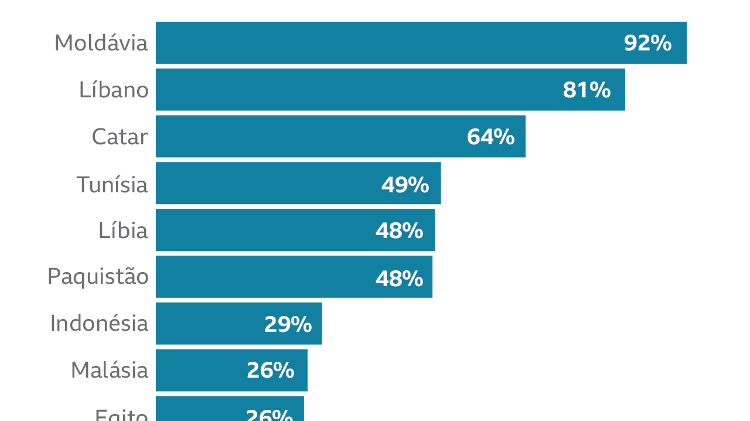

Some countries rely heavily on it. Lebanon imports 80% of its wheat from Ukraine and India imports 76% of its sunflower oil.

The UN World Food Program (WFP), which feeds people on the brink of famine in countries such as Ethiopia, Yemen and Afghanistan, supplies 40 percent of its wheat from this country.

Even before the war, the world’s food supply was precarious. Drought affected Canada’s wheat and vegetable oil crops and corn and soybean production in South America last year.

The Covid epidemic also had a great impact. Labor shortages in Indonesia and Malaysia meant lower palm oil harvests, which in turn pushed up vegetable oil prices worldwide.

Earlier this year, the price of many of the world’s staple foods was reaching record highs. Many had hoped that Ukraine’s crops could help bridge the global deficit.

But the invasion of Russia prevented this. Ukraine’s Ministry of Agriculture says 20 million tons of grain are currently stuck in the country.

Before the war, 90% of Ukraine’s exports were shipped from deep ports in the Black Sea, which could load tankers large enough to travel long distances to China or India and still make a profit.

But now they are all closed. Russia took most of the Ukrainian coast and blocked the rest with a fleet of at least 20 ships, including four submarines.

WFP chief David Beasley urged the international community to organize an escort to break the blockade.

“There’s a lot that can go wrong militarily without Russia’s understanding,” says Jonathan Bentham, a naval defense analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

An escort says it will require significant air, land and sea power and will be politically complex.

“Ideally, you would ask Black Sea countries like Romania and Bulgaria to do that to de-escalate tensions. But they probably don’t have the capacity. That’s why you should consider removing NATO members from the Black Sea.”

This will put Turkey, which controls the Black Sea Straits, in a difficult position. The country has already said it will restrict the entry of warships.

Russia’s offer to open a corridor for food shipments via the Black Sea in exchange for the relaxation of sanctions came after the European Union discussed the new sanctions package and showed no signs of change in the trend.

Bentham adds that since Ukraine has mines protected its coastline and strategically sank ships, it may take months or years to secure the Black Sea even if the war ends tomorrow.

For now, food can only be taken from Ukraine by land or from barges on the Danube.

Last week, the European Union announced plans to help by investing billions of euros in infrastructure. But Kees Huizinga, Stetsiuk’s neighbor? Who owns and cultivates 15,000 hectares? says the block isn’t doing enough.

He has been trying to transport goods since the beginning of the war and is infuriated by the paper pile required by the European Union, which he says has created lines of up to 25 kilometers across the border.

“It’s just paper, it’s not like they don’t actually sample the corn. You just have to have the paper,” he says.

On May 18, two days after the European Union’s announcement, customs officials asked their drivers for two forms they had never seen before.

“The border isn’t getting easier, it’s getting bureaucratic,” he says.

In the last three weeks, Huizinga has exported 150 tons of grain. The same amount can be shipped from the port of Odessa in a few hours.

“Open the borders” begs the European Union, “let go of the business”.

The main exit from the country is now the railway. But Ukraine’s rail system is wider than that of the European Union, meaning that loads have to be transferred to new wagons at the border. The average wait time is 16 days, but it can be up to 30 days.

While the global debate about food shortages is mostly about wheat, most of the grain currently leaving Ukraine is corn. There are two reasons for this, according to Elena Neroba, a Ukrainian grain analyst at brokerage firm Maxigrain.

He believes that Ukrainian farmers are hesitant to sell wheat because they do not recall the Holodomor, the widespread famine that struck Ukraine in 1932 during Joseph Stalin’s Soviet regime and killed millions of Ukrainians. Corn is not consumed much in Ukraine.

He says the other factor is demand. Europe does not buy much Ukrainian wheat, it is self-sufficient. It is difficult to transport this wheat beyond the European Union, as ports in Poland and Romania are not equipped to export large quantities of grain.

“Until July, EU countries will be busy exporting their own summer crops and will have even less capacity to process Ukraine’s food,” Neroba said.

Time is running out to solve the problem. Storage facilities are full and the summer harvest of wheat, barley and canola is weeks away.

Stetsiuk’s farm still has about 40% of last year’s harvest and very little room for next season.

“We don’t want to waste it. We know how important it is for the West, for Africa, for Asia,” he says.

“This is the fruit of our work and people need it.”

If he can’t sell the stock, he can’t afford to plant it this fall. He hopes the international community can help raise funds for Ukrainian farmers to restock grain and crops.

If they don’t, he says, next year’s grain shortages will be even worse.

Many wheat fields are now in particularly bad condition. Dry weather in Central Europe, the United States, India, Pakistan and North Africa means production will likely be low. In Ukraine, the weather is good for wheat.

Stetsiuk started her farm with her late husband 30 years ago when Ukraine was just beginning to rise from the ashes of the USSR. They were the first to buy farmland in their area, and in the process became a proud family of farmers. His two daughters and son are also involved.

“We want to keep doing that. We want to help people by providing food.”

In a few months, Russia says it takes at least 20 years.

source: Noticias