China’s crackdown has had repercussions abroad, adopting Twitter to target Asian journalists living in the West through a new network called Spamouflage, an analysis by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI, English acronym).

Researchers Danielle Cave and Albert Zhang, authors of the report, have identified coordinated online attacks against journalists, particularly ethnic Chinese women working for major media outlets, in recent weeks.

The social network acknowledged the attacks on Axios and said it suspended more than 400 accounts. The Chinese government has denied any involvement with Spamouflage, but ASPI lists several links to the country.

window.uolads.push({ id: "banner-300x250-3-area" });

Chinese crackdowns try to silence journalists abroad

The ASPI analysis, first reported by US website Axios, identified China’s effort to combat the work and views of notorious female journalists living outside the country.

The focus has been on professionals working in major Western media such as The New Yorker and The Economist, the New York Times and The Guardian newspapers, and the financial news website Quartz.

Examples of this are the attacks on the Twitter accounts of Jiayang Fan (New Yorker), Alice Su (The Economist), and Muyi Xiao (New York Times) last month. Many of the messages said they were “traitor” and “tarnish” China’s image.

According to the researchers, in addition to journalists, analysts and human rights activists from China, they are also the object of an “ongoing, coordinated and large-scale online campaign” that spreads hatred and incites the persecution of professionals.

Recently, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that organizations affiliated with the Chinese government began to harass foreign media professionals publicly, resulting in massive online and in-person harassment campaigns.

As part of this new tactic, state media and popular citizens on the social network Weibo are posting the names and photos of foreign journalists who “promote and attack China”, describing their news as “biased”, “dishonest” and threatening.

Read more

How China Is Using Its Citizens To Attack Foreign Journalists At Home And Chinese Journalists Abroad.

Based on the latest attacks, ASPI assesses that the fake Twitter accounts behind this operation against Chinese journalists are linked to the “Spamouflage” network, which the social network itself attributed to the Chinese government in 2019.

A Twitter spokesperson confirmed to Axios that the event identified in the ASPI report was part of the “Spamouflage” network.

The platform confirmed that the investigation into the coordinated attacks on Asian female journalists is ongoing.

How does spamouflage work?

ASPI researchers detailed how coordinated attacks of the “Spamouflage” network, the cyber arm of repression in China, work.

Hundreds of accounts were opened just to reach journalists. Some target just one professional, while other profiles target multiple women at once.

Some of these Twitter profiles also spread propaganda aligned with the Communist Party of China (CCP) in other posts not targeting women.

The most recent attacks have included mobbing, harassment, mass trolling and threats to media professionals – some of them Chinese and others of Asian descent but born abroad, according to the institute.

“Some women have been bombarded with tweets on a variety of topics from spam accounts, often blaming the target for fake news or anti-Chinese coverage, albeit often non-personalized.”

Other parts of “spamoufflage” attacks are much more complex and personalized.

ASPI explains that most content is tailored to individual circumstances, covering the professional and personal lives of victims. “This requires extensive monitoring of targeted people to tailor these tweets and their messages,” the report says.

read it too

Hong Kong’s free journalism ‘undermined’ by pro-Beijing state media, report condemns

On Twitter, victims are simultaneously starting to receive hundreds of messages accusing them of being traitors and liars, betraying their “homeland” and slandering their country of origin – even if they don’t have Chinese citizenship at all.

“These accounts are trying to attack your physical appearance, questioning your credibility and the quality of your work, often in response to the content they write or produce.

These campaigns are characterized by high levels of personal abuse, including sexist, misogynistic and racist attacks with messages such as “traitors don’t die well” and “traitors often end badly”.

One of them was the hashtag #TraitorJiayangFan, which was targeted at New York writer Jiayang Fan.

Fan wrote about exposure to Chinese propaganda and nationalist trolls.

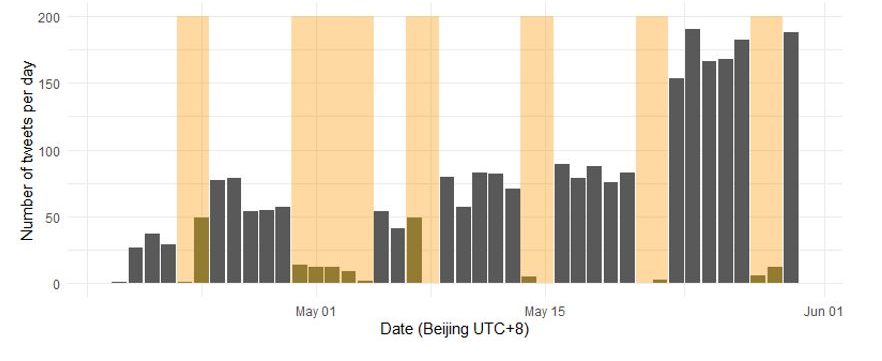

ASPI research showed that the most recent attacks with #TraitorJiayangFan have been initiated and powered by at least 367 fake Twitter accounts since April 19th.

Some Twitter profiles shared videos from dubious YouTube accounts, including, for example, alleged user Lino Nissan, who was created on May 25 and only posted videos attacking Fan in Mandarin.

Researchers have even found that many of the Twitter accounts of this hate network have dedicated images of real women from other sites to use as profile pictures.

Images produced with artificial intelligence were used as profile photos. These profile pictures are mostly of women, but in some cases of children.

Analysis links ‘digital printing’ to China’s online profiles

The ASPI report followed Twitter accounts attacking Asian journalists and even profiles from China.

The institute has found several similar patterns in profiles used to spread hate on women’s social media, including posting content denying human rights abuses in Xinjiang, sharing hashtags that ASPI considers “Spamouflage”, and using profile pictures similar to previous linked accounts. to the same network.

In addition, most attacks on Western media professionals were carried out during Beijing office hours.

And accounts were much less active between April 30 and May 4, the extended Labor Day holiday period in China.

According to the institute, New York Times reporter Muyi Xiao and Washington video journalist Xinyan Yu are currently the targets of some of the most malicious attacks.

Most of the Twitter accounts targeting them are linked to the same operators targeting Fan and other Chinese Communist Party-linked information operations.

Last week, at least 112 different accounts sent over 500 tweets targeting Xiao within 24 hours. Of these accounts, 54 were created on April 15 alone.

According to the report, this activity is increasing. False pro-Chinese Twitter accounts are starting to harass other notorious journalists and human rights activists, including Alice Su, Mei Fong, Lingling Wei and Jane Li.

These covert activities seem to be coordinated with a broader campaign by the Chinese government to silence women of Asian descent who criticize its policies or simply report on certain problems taking place in China.

This isn’t the first time the CCP has targeted women online. In China, women have been abused, censored, removed from the platform, and sometimes even arrested, for example, for their work on women’s rights.

Journalists working in China have long been targeted by authorities.

This is what happened, for example, with Australian journalist Cheng Lei, who was imprisoned for 21 months on Chinese soil. In a recent interview, her boyfriend said, Nick Coyle said he was in poor health due to a raw white rice diet and had not visited the consulate for several months.

The 46-year-old journalist is accused of “illegally supplying government records abroad”. He was a presenter for the state broadcaster China Global Television Network (CGTN), and his arrest caused an international uproar.

Read more

Boyfriend says Australian journalist arrested in China was fed raw rice and missed consular visits

Institute says governments and platforms must stop China’s crackdown

For the Australian institute, it’s up to the country’s governments and social media platforms to stop China’s repression online.

ASPI points out that the Chinese state is using more strategic global propaganda channels, mobilizing online nationalist activities, recruiting and empowering Western influencers, and amplifying Russian narratives and disinformation about Ukraine, i.e. broadening the Chinese government’s reach and social media targets.

For this reason, social media platforms urgently need to change their approach with coordinated attacks and adopt a more preventive and proactive stance:

“Platforms and governments must work more collaboratively to build the infrastructure, capacity and deterrents needed to respond to foreign cyber-intrusion and transnational digital pressure.

Both need to work more closely with civil society groups specializing in policy development and identifying networks, actors and targets.”

ASPI suggests it would be a good first step for governments to publicly condemn these malicious campaigns of harassment and disinformation against their citizens.

This will signal a rapid increase in policy focus and action to the public, diaspora communities, social media platforms, bad actors and of course individuals and organizations under threat.”

read it too

source: Noticias

[author_name]