When Russia invaded Ukraine, the outbreak of war caused a family of six adopted children to be separated. And parents, hearing about some cases of forced adoptions in Russia, feared that they would never see them again.

Shortly after the start of the Russian offensive at the end of February, Olga Lopatkina fell into a feeling of panic – she immediately thought of her six adopted children, who were traveling to the coast of Mariupol, 100 km from home.

They were at a summer camp by the sea. War broke out and the road to the seaside town became extremely dangerous due to heavy shelling.

Olga faced a terrible choice: ask her husband Denis to risk everything to get them out of there, or to leave the children in Mariupol. At that point in the war, the city still looked relatively safe.

“We started panicking and didn’t know what to do,” he says.

The complete destruction of Mariupol has become a symbol of the cruelty of the Russian bombardment.

The brutal reality of the war became clear to Olga just two days later when she encountered refugees from the east. He was shocked to see how quickly normal life deteriorated.

Like many people in Ukraine, Olga assumed that the war would be over in a few days or weeks and hoped that the children would be evacuated to a safe area by the Ukrainian authorities.

However, it soon became clear that the conflict had escalated and the children were in extreme danger. Olga was worried about the future of her Russian-controlled children, even if they survived the bombing.

Then came the news that civilians, adults and children were being transferred to Russia. Moscow called these transfers “evacuation”. However, Ukraine classified them as forced deportations, a practice similar to the Stalin era in the 1940s.

The couple started adopting in 2016. In February of this year, at the time of the outbreak of war, they had seven adopted children and two biological children, aged between six and 17.

“We’re crazy people, but we like it. Children give us feelings we wouldn’t have otherwise – life was empty before them,” she says.

Olga worked as a children’s music teacher and Denis from Minas Gerais. Their lives were happy and complete. But in early March, the family broke up and became frightened.

The electricity at the children’s shelter in Mariupol was cut off by bombings, and Olga’s children could no longer charge their phones and were out of touch with their mother.

At their home in the eastern city of Vuhledar, the Lopatkin family’s parents also took shelter in their basements as the war escalated. “We were bombed everywhere, it’s scary,” says Olga.

They decided to go to Zaporizhzhia, where some people were evacuated from Mariupol, hoping that the Ukrainian authorities would take the children there as well.

But the city was not safe. With no trace of the children left, the family decided to move further west to Lviv.

There a new problem arose: Denis could be drafted into the army. Against their will, they decided to flee Ukraine.

Less than two weeks into the war, Olga, Denis, and their three remaining children are refugees – but Olga says she never gave up hope of getting her children back.

The family was in Germany, and when they heard about the children, they decided where to move.

They were taken to a part of the Donetsk region controlled by pro-Russian separatists, where they were placed in a tuberculosis hospital. Because they had previously sought refuge in a sanatorium for patients with respiratory problems.

Social services said they were abandoned to children.

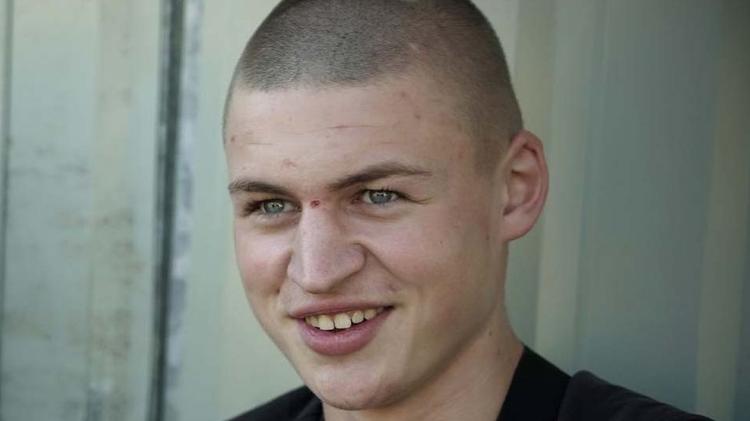

The eldest son, 17-year-old Timofey, managed to charge his phone and text Olga. He said he was offered to go alone, but refused to stay and take care of his siblings and was angry that he had left Ukraine.

“I realized they couldn’t take us from Mariupol, but it really pissed me off that they went abroad,” he says.

Feeling helpless, Olga continued to ask for help and information about her children on social media, but was often insulted. Many accused him of not doing enough to save the children and criticized him for leaving Ukraine. The accusations that she abandoned her children deeply hurt her.

He spoke to the international press to give his version.

“I’ve tried every way to publicize our situation, hoping someone would hear something and help,” she says.

Meanwhile, the couple was deciding where to settle in Europe. They chose the small town of Loue in northwest France, where they started new lives, found jobs and a home big enough for all the children subsidized by the Red Cross.

The mayor invited ten Ukrainian refugee families to move to the city with benefits for families with adopted children.

In early April, Olga and Timofey established a routine of talking on the phone with their children almost every night, which helped improve their relationship.

It was necessary to wait and hope that the Donetsk social services would agree to release the children, in the end they did too.

But it was not that simple. They said they would hand over their children only to their legal guardian, Olga. And he would have to go back to where he had just escaped.

“I was a refugee from the Russian Federation and now I have to go to the Russian Federation?”

For a while, it seemed like there was a stalemate. Donetsk social services required Olga to present the children’s birth certificates to prove their identity, but feared that this would lead to the children being put up for adoption.

This fear was well established. Russian television often broadcasts optimistic news about the “evacuation” of civilians from the “liberated” areas of Ukraine.

The Ukrainian government says this is forced deportation, which in the case of orphaned children amounts to kidnapping.

In May, Russian President Vladimir Putin issued a decree “simplifying” the issuance of Russian documents to Ukrainian children. Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the move violated the Geneva convention on human rights.

Earlier this month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said that as many as 2 million Ukrainians, including hundreds of thousands of children, were forcibly deported to Russia.

But soon there was a glimmer of hope in Olga’s condition. She got a call in June. There was someone in Donetsk who could bring their children to Western Europe.

Tatyana, an experienced volunteer working with orphaned children and vulnerable mothers in Donetsk, had a professional relationship with the authorities for many years and was willing to help.

Olga and Denis gave Tatyana the documents of the children along with a release form, making her their temporary legal guardian. They had to trust the volunteer blindly, but Olga says she thinks it’s the right thing to do.

Yet the process was not simple. It was only at the last moment that they learned that the documents were approved. Tatyana with the children went to Russia, and then to Latvia and Germany. Every border crossing was stressful.

“They all have different surnames, and the original release form was in French. I had to explain our situation to countless border guards several times,” Tatyana says.

He took the children to Berlin and handed them over to Denis, who took them to his new home in Loue.

After four months of uncertainty and anxiety, the family reunion was incredibly emotional.

Tears mixed with laughter as Denis first, then Olga embrace their child, who still can’t believe they’re actually seeing them.

Olga continued to hug the children, “Let me see you, let me see you! You’ve grown so much, I haven’t seen you in a long time!”

Timofey refrained from showing affection: “I’m really glad everything went well, but I’m also older so I don’t show how happy I am. I’m glad we’re together again, and I kept my word and brought the kids to their parents.”

Olga is eternally grateful to the woman she has never met and describes as “our hero”.

Now the family is planning a well-deserved vacation. Olga wants to travel to Portugal.

“I’ve never seen the sea,” he says. “Of course we’ll all go together. I’ll never let them out of my sight again.”

cooperated Anastasia Lotareva and Alexey Gusev. Photos by Vladimir Pirozhkov.

– This text was originally published at https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-62204717.

source: Noticias

[author_name]