Myths and mysteries surround the ancient Tartessian society mixed with the legendary Atlantis.

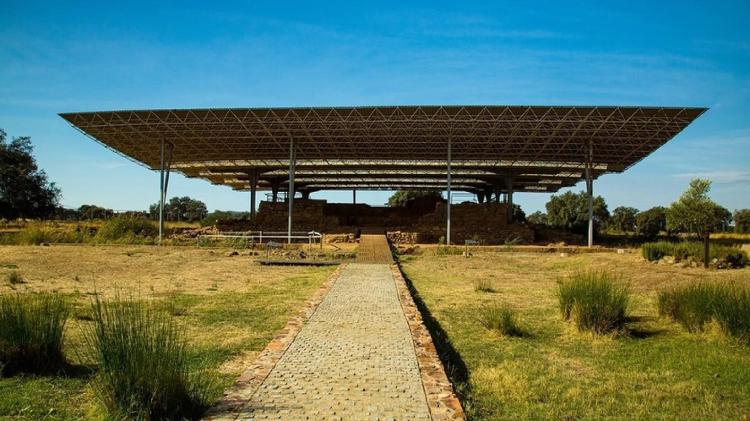

After walking on a gravel road surrounded by dry plains, I finally arrive at the Cancho Roano archaeological site in the valley of the Guadiana River in the region of Extremadura (southwest Spain).

As I watch, I wonder how different this flat, barren, dusty land looked 2,500 years ago when the Tartessians, a mysterious society that flourished on the Iberian Peninsula between the 9th and 5th centuries, was the center of trade and worship. B.C. until it suddenly disappeared.

Today, continued research with new technologies is bringing more insight into the lost civilization and its role in Iberian history.

Who were the Tartes?

Thousands of years ago, Greek and Roman texts spoke of Tartessus, but conflicting descriptions—and a long-standing lack of definitive archaeological evidence—prevented modern archaeologists and historians from fully describing what Tartessus was: a city? a kingdom? river?

The 5th century BC Greek historian Herodotus mentions a port city beyond the Pillars of Hercules (now the Strait of Gibraltar); this has led some researchers to imagine that Tartessus was a body of water, and others that it was (possibly) a harbor. On the south coast of Spain, near the present-day city of Huelva).

There were also theories that Tartessus was the legendary Atlantis. Inspired by Aristotle’s texts, these theories were largely rejected by the scientific community.

Today, the Tartessians are generally considered to be a civilization consisting of a mixture of the indigenous people of the Iberian Peninsula and Greek and Phoenician settlers. They were wealthy thanks to their vast mineral resources and a thriving commercial economy.

Early discoveries led historians to believe that civilization was concentrated around the Guadalquivir River valley in Spain’s Andalusia region, but more recent discoveries in the Guadiana River valley (further west, near the Spain-Portugal border) have made archaeologists rethink the large capacity. tartes.

In total, more than 20 Tartessian sites have been identified in Spain. Three of them were excavated in the Guadiana valley: Cancho Roano, Casas de Turuñuelo and La Mata.

Cancho Roano’s site

Archaeologists discovered Cancho Roano in 1978. The site has uncovered yet another piece of history.

It contains the remains of three Tartess temples built in sequence, each oriented towards sunrise, each on the ruins of the previous one. An interpretation center explains what is known about the history of the temples and the artifacts found inside.

The mud-brick walls of the more recent temple (built towards the end of the 6th century BC) enclose 11 rooms covering an area of approximately 500 m².

But for reasons still unknown to archaeologists, at the end of the 5th century BC, the people living there performed a ritual in which they ate animals, threw their remains into a central pit, set fire to the temple, sealed and sealed with clay. abandoned, leaving a series of burning objects inside, such as iron tools and gold jewellery.

“The discovery of Cancho Roano was a revolution in Iberian archaeology,” says Sebastián Celestino Pérez, who has led the excavation for 23 years and is now a researcher at the Instituto de Arqueologia de Mérida, Spain.

He explains that the walls, altar, ditch, and artifacts (such as jewellery, glass, and warrior stele) at the site were well preserved despite the fire, and that many scholars do not believe such a site could be found outside of Andalusia. , where all previous evidence was discovered.

animal sacrifice

The archaeological site of Casas de Turuñuelo has only been studied in recent years after its discovery in 2015.

It is the best preserved proto-historical structure in the western Mediterranean (since prehistory and interhistory) and is the largest animal sacrifice site in the region – more than 50 animals. The site helps scientists learn more about the Tartessian culture.

“Turunuelo [foi] a sanctuary where animals are also sacrificed and thrown into a pit,” says Celestino Perez. He states that this place was burned and covered with clay like Cancho Roano.

“But Turuñuelo has another, more ostentatious function – as a symbol of power. It is from the same era as Cancho Roano, but the construction techniques used in Turuñuelo are much more advanced and the materials are richer, brought from various places in the Mediterranean,” explains the researcher.

Using a new technology called photogrammetry, archaeologists take pictures of the ruins in Turuñuelo and use software to combine them to create 3-D images that virtually recreate the buildings.

This process helps them understand the types and techniques of construction as well as the materials used. With this, the remains of Turuñuelo are known to be Tartess, not Roman as previously believed.

The La Mata site was found in 1930, long before the other two. But the similarities are striking, and the approach now taken at Turuñuelo may reveal more of its secrets.

“The most surprising thing to me is a very strange habit. [dos tartessos] According to Ana Belén Gallardo Delgado, historian and guide at La Mata, the same procedure was followed in order to demolish their house, namely in all the areas found: emptying all vases and amphorae, burning the building and burying it”.

“I hope that with the new technologies it will be possible to explain a lot more about the origins of this civilization and analyze it a little more about the way of life,” he says.

“The Tartessian presence in Extremadura is becoming more and more important thanks to new developments in archeology. It is also believed that eight more tombs have been found in the Badajoz area. [também na Extremadura] There may be Tartess structures like those excavated before.”

While research continues at the Extremadura archaeological sites (Cancho Roano and La Mata are open to the public), history buffs can also view Tartess tools, horse figurines and ornate ivory at the Badajoz Archaeological Museum.

The museum is located inside the Moorish fortress of the Alcazaba, close to the Portuguese border, built on top of a hill in the 12th century and surrounded by manicured gardens.

first posts

While viewing a gallery devoted to Spanish prehistory, curator Celia Lozano Soto pointed to a stele (stone column) carved with Tartess inscriptions, the first known written record from the Iberian Peninsula.

“The language is still being studied and translated,” he says. “It’s a mix of different things that makes it unique.”

An interesting writing from the 8th century BC is derived from the Phoenician alphabet. It’s a palindrome – it can be read from right to left or vice versa, but the sounds each symbol represents are still unknown.

In addition to language, mass sacrifices, and fires, there is another great puzzle with the Tartessians: Why did this civilization suddenly disappear about 2,500 years ago?

The end of the Tartess civilization

Eduardo Ferrer-Albelda, a professor of archeology at the University of Seville in Spain, said any reduction in trade could create tensions, as the Tartess society is rich in metals.

“There are also records of a mining crisis, but violence must have played a significant role,” he explains.

“Cooperation between the Phoenicians and local aristocracies may have ended abruptly, indicating that an anti-Phoenician and anti-aristocratic movement may have taken place among the population of the Tartessian region.”

Celestino Perez advocates another theory. According to him, “at this time there may have been an earthquake in the mid-6th century BC, followed by a tsunami that would hit the main Tartessian ports. This may have been the reason for the rapid decline of the Tartessians”.

It is important to understand why civilization disappeared, but the sociocultural influence of the Tartessians is the focus of current research.

“It seems that the Tartessian port of Huelva has been found. If confirmed, this could be a giant step towards understanding the Tartess trade network. And the so-called Tartess tombs in the Guadiana valley” [Cancho Roana, Turuñuelo e La Mata] seems to be the key to getting to know this culture better”, explains Celestino Perez.

Read the original version of this report (in English) on the website BBC Travel.

source: Noticias

[author_name]